Are interest rates the right monetary tool to fight fiscal-driven inflation?

Inflation today is caused by rising fiscal deficits; raising interest rates will further aggravate inflation as interest payments balloon & deficits widen; but cutting rates isn't an option either.

The Monday Macroview at a Glance:

At the start of the pandemic, the US monetary and fiscal policies joined forces together to save the US economy out of the trenches of what could have been a severe depression.

While the US economy recovered at the fastest pace in modern history in response to the largest fiscal stimulus, the process created inflation. That too, the highest level in over 40 years.

Since then, the Fed’s aggressive monetary policy has successfully drained reserves from the banking system as bank lending has contracted, and S&P 500 has stalled since 2021. Consumers are also starting to feel the pain.

So, can we declare that the Fed is on its path to victory to demolish inflation long term?

Not so fast! The Fed is using a 1970s playbook to cure 2020s inflation when the root causes of inflation in these two periods of time were completely different. The 1970s inflation was led by a spike in bank lending, whereas the 2020s inflation is driven by an increase in fiscal deficits.

The longer the Fed raises rates, it creates a “tug of war” between the deflationary forces of bank lending contraction and the inflationary forces of ballooning government debts due to higher interest payments.

But, what choices does the Fed have? Read below to find more.

Monetary and Fiscal Policies joined forces together to save the US economy during the pandemic.

March 11, 2020: The World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid 19 a pandemic.

March 13, 2020: The US declared a national emergency and issued a travel ban on non-US citizens from entering the country.

March 15, 2020: The Fed cut its Fed funds rate to 0-0.25%. Furthermore, the Fed shifted to supporting the economy with its Quantitative Easing program, where it said it would buy at least $500B in US Treasury securities and $200B in Mortgage-backed securities over “the coming months”.

March 23, 2020: The Fed declared that it would buy securities “in the amounts needed to support smooth market functioning and effective transmission of monetary policy to broader financial conditions”. On the same day, the S&P 500 found its bottom at 2191 after crashing -35% from its highs of 3380.

March 25, 2020: The Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES) was passed into law, making it the largest economic recovery package in history. The bipartisan legislation provided direct payments to Americans and expansions in unemployment insurance.

August 21, 2020: The S&P 500 reached a new all time high of 3413.

5 months is all it took to reflate the economy out of a severe depression into growth mode.

This period of time was defined by a massive shot of adrenaline in the form of the US Fed “printing reserves” to buy US Treasuries issued by the government. The US government then handed the money to the people, in the form of checks. This raised peoples’ received income to record levels, even though their earned income had collapsed. That income then went into a) spending, b) paying down debts and c) the purchases of financial assets.

Thus, the US economic flywheel kept turning, and the US economy was able to get out of recession at the fastest rate ever in history.

But, at what cost?

While the US was able to recover from a recession at the fastest rate in history, the real economy money created by the government in the form of debt that was financed by the Fed, undeniably created some undesired consequences.

Inflation! That, too, the highest level in more than 40 years.

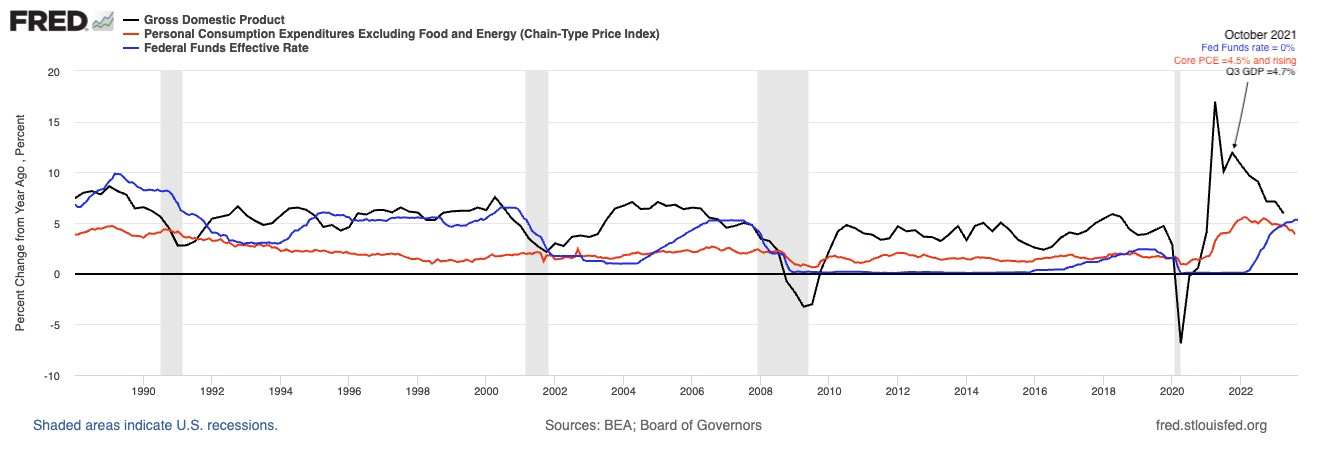

By October 2021, Core Inflation was at 4.5% YoY (higher than the Fed’s long term rate of 2.2%) and Real GDP had fully recovered at 4.7% (which meant Nominal GDP was above 8%). Meanwhile, the Federal funds rate was kept at 0%.

The idea: Inflation is “transitory”, caused by supply chain shocks. And it will correct itself when supply chain disruptions ease.

Did they? On the contrary!

With the Fed’ asset size at $8.5T, US Federal Debt-to-GDP at 122%, and interest rates at 0%, risk assets rallied. S&P 500 reached an all time high of 4800 by the end of 2021.

Consumer Spending was up 12.9% YoY in Oct 2021, led by Durable goods spending. Consumers were just starting to shift their spending share from durable goods to services, as the economy was opening up.

With mortgage rates at 2.99%, Home prices were up 19% on a YoY basis.

At an unemployment rate of 4.5% in October 2021, Job Openings started to grow at a faster rate than the quantity of labor. In October 2021, the ratio of Job Openings to Unemployment level reached 1.5, the highest ever recorded until then. The ratio of Job Openings to Unemployment level would eventually climb to 2.00 until March 2022. This put upward pressure on wages.

As wages grew, along with excess savings from the pandemic, inflation continued to grow in the US economy at full force until March 2022, when both average hourly earnings and core inflation peaked.

The Fed rushed into the crime scene to quell inflation and save its credibility by increasing interest rates and reducing its balance sheet

The Fed decided to reverse its stance on the “inflation is transitory” narrative by the end of 2022. Since then, the Fed has hiked interest rates to 5.25-5.5% and also reduced its balance sheet size by $815B since June 2022.

However, since the last FOMC meeting took place on September 20, 2023, the bond market has had a panic attack. What changed?

Up until now, the bond market believed that the Fed, while keeping rates high to quell inflation, would start to cut rates meaningfully by 2024. The expectation was reversed as the Fed updated their projections on the US economy. They now the expect the following:

Real GDP:

Real GDP is now expected to grow at 2.1% YoY in 2023 vs. previous projection of 1.0%.

In 2024, Real GDP is expected to grow at 1.5% YoY, vs. previous projection of 1.1%.

Unemployment Rate:

Unemployment rate is expected to grow at 3.8% in 2023, vs. previous expectation of 4.1%. In other words, the labor market is expected to remain much more resilient than previous estimations.

Unemployment rate is also revised lower from 2024 and 2025 to 4.1% vs. previous expectation of 4.5%.

Fed funds rate:

While the Fed funds rate projection for 2023 is unchanged, it moved up considerably for 2024. The Fed is now expected to hold rates at 5.1%, vs. previous expectation of 4.6%.

The Fed is expected to hold rates at 3.4% in 2025 vs. previous expectation of 3.1%.

Real Fed Funds rate:

Given the Fed’s projection for Core PCE (as outlined in the dot plot below), the Real Fed funds rate is now projected to be at 1.9% in 2023 (vs. 1.7% in June 2023 projections), 2.5% (vs. 2%) in 2024 and 1.6% (vs. 1.2%) in 2025.

Since the tightening cycle began, the 10Y US Treasury bond has climbed from 1.5% in October 2021 (when the Fed Funds rate was 0%) to 4.8% in October 2023. As the tightening cycle became deeper in 2022, the yield curves inverted.

Today, while the yield curve is still inverted, the yields at the long end of the curve have gone up sharply, as bond investors reset the pricing of the longer term bonds based on the Fed’s updated economic projections which point to rates to be kept higher from longer.

Liquidity is tight, Bank lending is weak, risk assets have stalled and the US consumer is starting to show signs of weakness

As the Fed projects interest rates to be kept higher for longer, it is also reducing its balance sheet size at the fastest rate in history. It has already trimmed its asset size by $815B since it decided to reverse its QE policy. Bank lending has already slowed down. The situation gets further aggravated when bank deposits start to flee, looking for higher yields in short term money market funds and US Government notes. This causes the bank reserves to go down further.

At the same time, the US Government is projected to issue $852B of net new debt between October to December 2023. Since the Fed is not buying, it is naturally the banks and the private sector that have to absorb the government debt (depending on their maturity dates), which is further negative for liquidity. As a result, there is increasingly limited liquidity that can be allocated to risk assets, such as equities. This is reflected in the S&P 500 index that has now stalled since 2021.

The US consumer is also starting to feel the pain. While the labor market is still resilient, a lot of the tailwinds driving consumer resilience are starting to fade away.

The boost from the pandemic checks have faded.

Consumers are taking on an increasing amount of loans to finance their spending in a high inflation and interest rate environment. At the same time, credit card delinquencies are starting to show.

Consumers faced with high mortgage rates are delaying their home purchase decisions, as mortgage applications continue to decline.

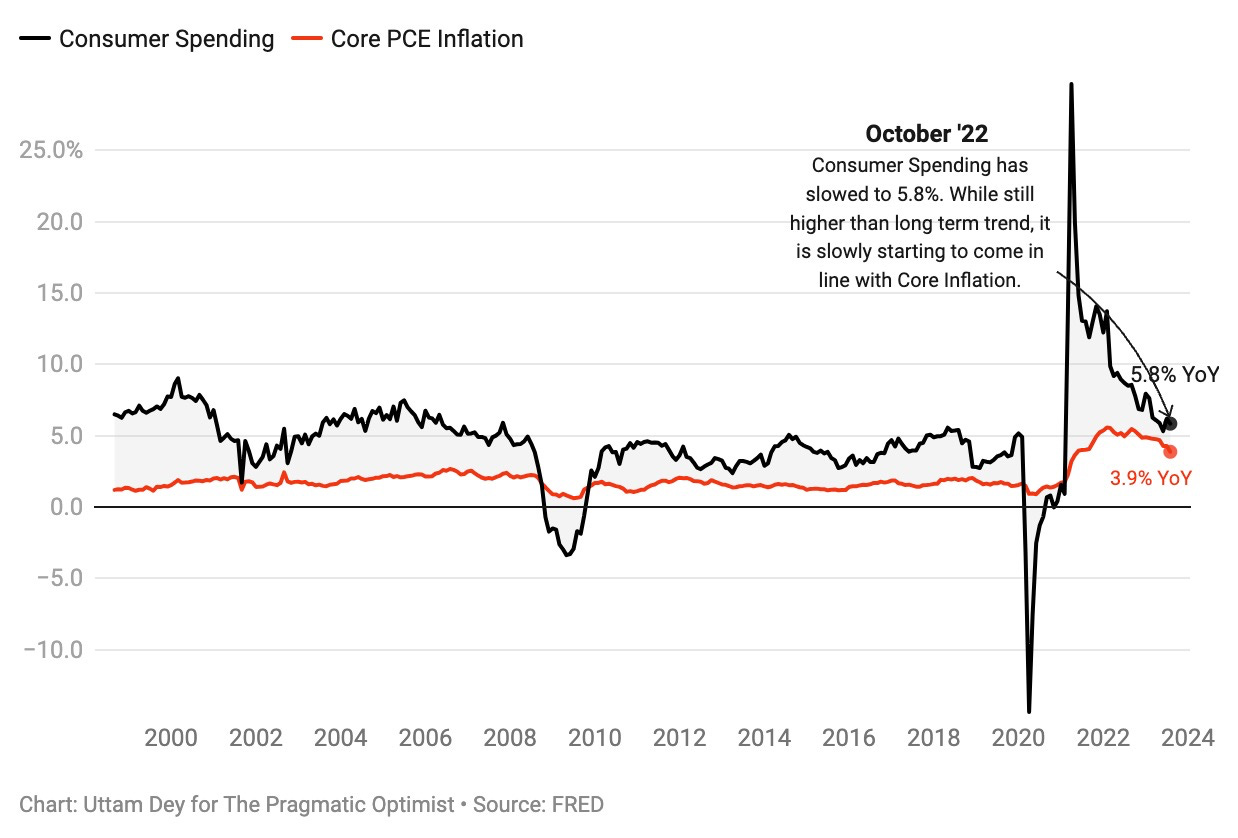

Nominal spending is slowly starting to come in line with long term inflation expectation.

So, does this mean that the Fed is on a successful path to fixing inflation long term?

The Fed is treating 2020s inflation with a 1970s playbook, when the causes of inflation during these two periods of time are completely different

In the current financial system, the majority of broad money creation happens due to a combination of fiscal deficits and bank lending. The magnitude of these two sources of real-economy money creation changes over time.

In the 1940s and 2020s, most of the money supply growth originated from fiscal deficits. In the 1970s, most of the money supply growth originated from bank lending.

In June 2023, Lyn Alden had extensively written on this topic, and I will borrow some of her work to build my perspectives on this matter.

Lyn had shared the following charts that show the 3-year rolling average of US fiscal deficits, new bank loans and the broad money supply. In this chart, you can see the broad money supply growth was driven by a spike in fiscal deficits during the 1940s (because of World War 2) and a growth in loan creation in the 1970s.

When we add in the layer of CPI inflation, we can see that inflation follows the direction of money growth, regardless of whether the money growth originated from fiscal deficits or bank lending.

We can finally add in the final piece of the 3 Month Treasury yield (a proxy for the Fed funds rate) to complete the picture of the state of money growth, inflation and monetary policy.

Today, the Fed Chair Jerome Powell is treating the 2020s inflation, in a similar fashion to the 1970s style inflation. These two periods of high inflation were caused by two separate reasons. The 2020s inflation is caused by a rise in fiscal deficits (which is still growing). On the other hand, the 1970s inflation was caused by a spike in bank lending. Today, Jerome Powell is raising interest rates to quell bank lending, even though bank lending wasn’t the cause of inflation in this cycle.

Why do interest rates fail to work when inflation is caused by fiscal deficits?

If inflation is caused by fiscal deficits, high interest rates turn out to be an ineffective tool. A central bank and the commercial banking system are forced by law to finance its government's fiscal deficits. By financing the government's fiscal deficits, real economy money is created.

By raising rates, the Fed can still slow the rate of inflation by draining reserves from the banking system and slow bank lending, even as fiscal deficits keep pouring in. This is what is happening today. In doing so, the Fed is simply offsetting the ongoing inflationary effect of the primary source (fiscal deficit), by subduing other factors (bank lending) that did not contribute to inflation in the first place.

There are immediate negative consequences of such a policy framework. The longer the Fed keeps its rates high, interest expenses on government debt grows. This means that the government is now dealing with ballooning interest payments on its debt. This will in turn result in even bigger fiscal deficits, which ironically pushes more “real economy money” into the economy. As per CBO’s projections, US government deficit is expected to double in the next 10 years.

In the 1940’s, when inflation rose due to the rising fiscal spending on World War II, the Fed had decided not to raise rates. The Fed and the commercial banking system were obligated to monetize the fiscal deficits anyway during the war. Had the Fed raised rates, it would have simply increased the government’s interest expense, which would mean higher deficits would need to be monetized, pushing more money into the economy. As a result, they decided to hold rates below the rate of inflation. When the war stopped, the fiscal deficit spending stopped. As a result, the rapid money creation stopped, which meant inflation came down to pre-war levels.

In summary, when inflation is driven by fiscal deficits, higher interest rates would only increase government’s interest expense, which would result in further widening of deficits, which then adds more real economy money, and the vicious cycle continues.

Does this mean the Fed should pause and reverse its monetary policy? It is complicated

The hardest inflation battle for a central bank (which is what the Fed faces today) is a combination of the following:

High sovereign debt-to-GDP ratio

Large and structural fiscal deficits tied to aged demographics and military spending

Resource constraints led by tight commodity and labor markets.

As per Congressional budget office, the projections for the path of the US government debt will follow its course below:

The US government debt is expected to rise in relation to GDP, mainly because of increases in interest costs, growth of spending in major healthcare programs and Social Security.

Outlays are expected to exceed their 50-year average during each year of the projection period. Revenues are expected to increase from their 50-year average after 2025 because of scheduled changes in tax law. However, the divergence between outlays and revenues will continue to grow, requiring the US government to issue incrementally higher debt every year moving forward.

Today, since the Fed is treating the current inflation period with a 1970s playbook by raising rates at the highest level and at the fastest pace in 40 years, they can certainly reduce money creation from bank lending in the intermediate term, but ironically exacerbate inflation due to further widening of the fiscal deficits, and deficit-induced real economy money growth in the longer term.

So far, that is what is playing out. In 2022, government tax revenue suffered as asset prices stagnated in 2022, leading to weak capital gains. Meanwhile, higher interest expense increased government spending, and thus the deficit began re-widening as interest rates started going up since last year.

At the same time, if the Fed chooses to bring out the 1940s playbook, and keeps interest rates low despite high inflation, it will reduce fiscal-driven inflation a bit. But the US dollar will be attacked, as people would borrow dollars at a comparatively low rate of interest and use it to buy harder assets, such as gold and real estate. The US dollar will severely weaken as a result, thus causing import price inflation, especially given that the US has been operating in trade deficits since 1994.

As the Fed raises rates, it creates a “tug of war” between the deflationary forces of bank lending contraction and the inflationary forces of ballooning government debts. Is there a way to solve the dilemma?

Capital controls is one of the most common ways to solve the dilemma, though I don’t think the US government would implement such a program anytime soon. The motivation behind capital controls is to reduce interest rates to quell fiscal-driven inflation, while also avoiding speculative attack on the currency. Essentially, if a nation implements capital controls, it would reduce the various ways to borrow money using the nation’s currency to buy private assets, while mandating institutions to buy government debt at interest rates that are below inflation rate and closing the various exist doors that people turn to in order to avoid holding the devaluing currency.

For example, in the 1940s, the United States (and other countries) had strict capital controls, in the form of banning Americans from owning gold and making it hard to transfer money globally.

The problem with capital controls is that it is a highly political matter. Also the nature of its top-down command naturally creates the underlying sentiment where capital keeps wanting to escape if possible.

Closing Thoughts

The combination of high fiscal debt and structurally tight resource constraints in the form of labor supply and commodities, is why I believe we may have entered a new era altogether, where inflation will be considerably stickier than in the past decade.

While we may be about to unleash a wave of productivity growth driven by technologies in AI, I still remain cautiously optimistic in this environment.

If we get inflation under control by having a recession, and then stimulate our way out of that recession and have another round of above target inflation because of it, then that is not really fixing the problem. In that case, we would simply be bouncing between inflation and stagnation.

Would love to hear your thoughts? Please feel free to leave your comments and feedback in the comments section below.

Have a great week!!!

Amrita 👋🏼👋🏼

It looks like the grass isn't green on either side for the economy.

The Fed will probably not be long before it is forced to pivot. In fact, this is the right timing for the beginning of the recession. The measures to climb out of the hole will be epic and will cause another inflationary wave much worse than the previous one.