Part 2: The Fed is broke: How the Fed creates and destroys money?

Real-economy money vs. financial-economy money, QE ≠ money printing, how the Fed deploys QE and QT to create and destroy reserves that affects long term interest rates and macroeconomic conditions

At a Glance

There is a common misconception that the Fed prints the money that we use in the economy. This post is written with the purpose to bust all the myths about how money is created and destroyed in the economy.

There are 2 tiers of money: real-economy money and financial-economy money.

Real-economy money is created by commercial banks in the form of lending and by governments in the form of deficit spending to fuel economic growth. Real-economy money is held by the private sector, which are households and businesses in the form of bank deposits and cash.

Financial-economy money is created by the Fed to increase reserves in the banking system, that facilitates the banks to transact with each other and settle transactions in the repo market.

The Fed creates bank reserves, by buying an existing US Treasury bond from the bank’s balance sheet and crediting the equivalent dollar amount in the bank reserves. As a result, creating bank reserves do not create real-economy money. During Quantitative Easing, the Fed creates bank reserves. During Quantitative Tightening, the Fed destroys bank reserves.

When the Fed destroys bank reserves, the banks have to accommodate newly issued bonds with a lower supply of reserves. Read below to find out how much further can the Fed reduce its balance sheet, before it severely impacts bank reserves, triggering a possible banking contagion.

🍂🍂🍂Happy October, fellow readers!!

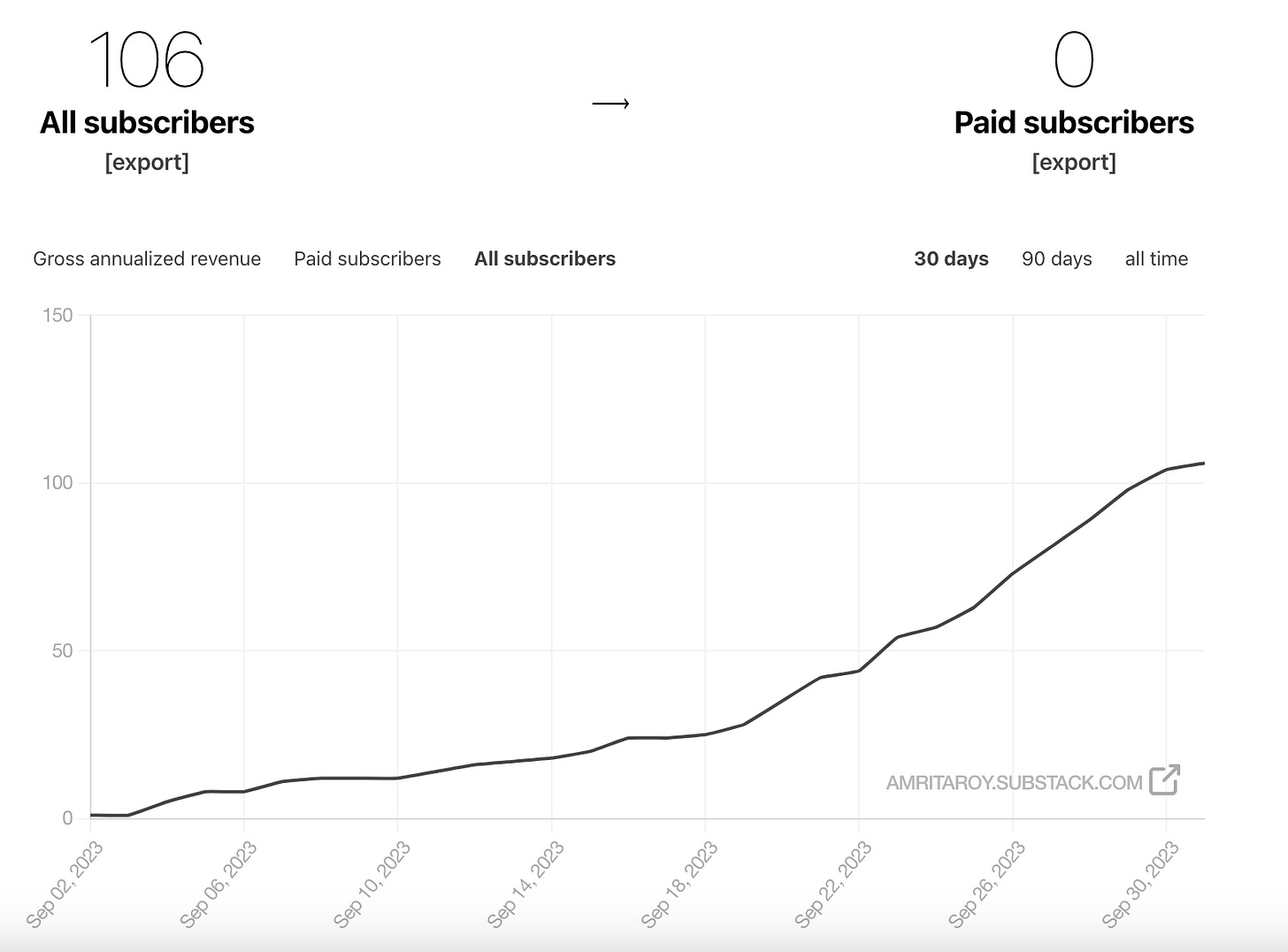

As I enter Week 4 of writing The Pragmatic Optimist, I wanted to take a moment to recognize everyone who has subscribed and thank you for your kind support. 🙏🏽

I am officially at 100+ subscribers, and it is a delight to write for you all for the last 3 weeks.

Over the last 3 weeks, I have connected with some very supportive readers and incredible writers/contributors on this platform , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , . It truly feels great to be building a community here on substack.

Here’s to many more exciting posts, partnerships and building a bigger and more engaged community! 🍻

🛎️ An important update to today’s post!

Last week, I set the expectation that I would publish Part 2 of “The Fed is Broke” edition today (Monday, October 2nd), that would detail how a “broke Fed” affects its nation and its people and what possible actions can the Fed take today to become profitable again.

Resetting expectations: When I started writing today’s post, I realized that “The Fed is broke” edition is better with 3 parts (instead of 2). Therefore, in order to set the right foundations in place, I decided to spend today’s chapter to explore how the Fed creates and destroys money in the economy.

The updated plan: This is the most updated version of “The Fed is Broke” edition, which is now divided into 3 parts.

Part 1: The Fed is broke: How it happened? Status: Already published .

Part 2: The Fed is broke: How the Fed creates and destroys money?

➡️➡️➡️ Status: This is what today’s post is about.

Part 3: The Fed is broke: Why it matters and can be done to fix it?

Status: To be published on October 8, 2023

In case you missed…

On Monday, last week, I wrote How the Fed went broke. Before we jump into how the Fed creates and destroys money in today’s post, I wanted to do a quick recap of Part 1, so that we are all on the same page.

Key Highlights from the previous post:

The Federal funds rate stands at 5.25-5.5%. This is the highest Fed funds rate since 2000. In the meantime, the Fed is also shrinking its balance sheet by allowing $95B worth of maturing bonds to roll off every month. So far, the Fed has cut it balance sheet size by $815B since June 2022. The balance sheet size currently stands at $8.02T ($4T higher than pre-pandemic levels).

The pace of interest rate hikes and the composition of maturity periods of assets and liabilities on the Fed’s balance sheet have resulted in the Fed now paying more on its liabilities (bank reserves, reverse repos) v.s earnings from its assets (US Treasury bonds, Mortgage-backed securities). This has resulted in the Fed operating at a financial loss, since Sep 2022.

When the Fed was profitable, the Fed’s net operating income (after paying for operating expenses and dividends to shareholders) would be transferred over as remittance to the US Treasury, as per regulation. In fact, the US Treasury would on average receive $100B from the US Fed as remittance until 2022, which would help pay a portion of the fiscal deficit.

Today, the source of remittance from the US Fed has vanished. The operating losses that the Fed is incurring is accounted as “deferred assets” on the Fed’s balance sheet, which is the total amount that the Fed would pay itself first, before they would return to sending remittances to the US Treasury.

While the Fed still has $44B of net positive equity (Assets-Liabilities = $44B) on paper, the equity figure turns negative if you don’t factor in the accounting relief from the “deferred assets”. That would make the US Fed technically broke.

This is the first time in modern history where the world’s largest central bank is not only operating at a financial loss, but is also technically broke.

Real-economy money vs. Financial-economy money

We often think that the Fed (or central banks, in general) print the money we use. Wrong. ❌

Our monetary systems runs on 2 distinct tiers of money:

Real-economy money

Real-Economy money is created by commercial banks and the government.

Real-economy money is used by non-financial private sector agents (for example: households and businesses).

Real-economy money is used to make transactions that contribute to economic activity.

If real-economy money grows faster than the supply of goods and services, it will lead to inflation.

Today, bank deposits held by the non-financial private sector and cash represent real-economy money.

Financial-economy money

Financial-economy money is created by the Fed (and other central banks, globally).

Financial-economy money is money used by financial entities, such as banks, asset managers, etc. to settle transactions and buy securities.

Financial-economy money can sometimes lead to asset price inflation (such as equities, bonds, etc.).

The mechanics behind real-economy money creation

Real economy money is created through bank lending. When a loan is made, a deposit is created simultaneously for the loan amount. Let’s say, I take out a loan for $100 from Bank ABC to buy a car. In this case, Bank ABC will enter a loan value of $100 in its asset side of the balance sheet, while simultaneously creating a deposit of $100 in its liability side of its balance sheet. Here’s how it works:

The above illustration depicts all the players involved in the real economy and what happens in the balance sheets of all the players in the economy when the commercial loan is created.

The real-economy has 3 players: the government, the commercial bank and the private sector (households and businesses).

When I borrow $100 from Bank ABC, the transaction takes place between me (i.e. the private sector) and the commercial bank. The government doesn’t play a part in this transaction.

This is what is happening on the bank’s balance sheet before and after creating the loan:

When the bank agrees to lend me $100, it enters $100 on its asset side of the balance sheet. Now, its assets have grown from $300 (before the loan was created) to $400 (after the loan is created).

On the liabilities side, there was $300 of deposit to begin with. But, after the loan is created, my account is credited with $100, with which I buy the car from Dealership XYZ. Now the Dealership XYZ has $100, which it got from selling the car, which it takes to deposit in the bank. As a result, the bank now has total deposit size of $400 ($300+$100)

This is what is happening on the private sector’s balance sheet before and after creating the loan:

The private sector had $300 in deposits, before the loan was created. After the loan is created, Dealership XYZ has $100 in its deposits, which is now added into the system. Therefore, the total deposit size is now $400. So, after the loan, the asset side of the private sector increased by $100.

Before the loan was created, the private sector already had $100 in loans (to pay back). After the loan, the private sector has an additional $100 in loan to pay back. Therefore, the total liabilities of the private sector has increased to $200, from $100 initially.

Net result: The net worth of the private sector before the loan was created was $200. The net worth of the private sector remains unchanged after the loan is created (as assets and liabilities cancel each other out). However, Bank ABC has now expanded its balance sheet to $400 (from $300 initially), as a result of creating the loan. We now have a net new $100 (out of thin air) that is circulating in the system.

The other real-economy money printer is the government. How come?

💡💡💡Think about it: When the US government sent checks to American citizens during the Covid 19 pandemic, it issued debt to finance the checks. The commercial banks purchased/financed the US debt issued, which resulted in the banks expanding their balance sheet. Once the debt was financed (by the commercial banks), it enabled the US government to deposit checks in people’s (private sector) bank accounts. Deposits are private sector’s assets. As a result, when the US government deposited checks in people’s accounts, their assets grew, while their liabilities remained unchanged. This boosted the net worth of the American people (the private sector) and created real-economy money. This is unlike bank lending, where real-economy money is created, without an additional boost to the net worth of the private sector.

How about financial-economy money? How is financial-economy money created? Who creates it and how does it all work?

What role does the Fed play in printing money?

We often think that a large central bank balance sheet, as is the case for the Fed, whose balance sheet size sits at $8T (down from a high of $8.9T in May 2022), implies that the central bank is “printing money”. That is not “fully” correct.

The truth is the Fed prints “reserves”, which is not the same as “printing real-economy money” that commercial banks do. What does that even mean?

During the Covid 19 pandemic, the Fed announced that it would perform Quantitative Easing (QE), where it would buy a combination of US Treasury bonds and Mortgage-backed securities. While the rate at which it performed QE changed during the period between March 2020 and May 2022, it increased its holdings of US Treasury bonds and Mortgage-backed securities (on its asset side) by 2x to $5.76T and $2.71T respectively.

So, in the process of doubling its assets (through the process of QE), the Fed didn’t actually “print money”?

When the Fed purchases US Treasury bonds and Mortgage-backed securities, the Fed’s asset size increases. Similar to how a commercial bank operates, it simultaneously “creates” money in the reserve accounts of the commercial banks to compensate them for the bond that it purchased (for every asset, there is a liability; akin to for every loan at a commercial bank, there is a deposit). Remember, bank reserves are liabilities for the Fed, since these are commercial banks parking their money at the Fed that earns an overnight interest rate.

However, unlike a commercial bank, that conjures up money out of thin air (based on regulatory capital requirement), when creating a loan on its asset side, the Fed does not do the same with QE. QE is not “printing money” like how a commercial bank “prints real-economy money”. QE is “printing reserves”, which is financial-economy money, that allows the banking system to function properly. Let me explain.

During QE, the Fed is buying a US Treasury bond from the commercial bank, which is equivalent to a dollar by “printing” a dollar in the bank reserves. The important thing to note is that these US Treasury bonds were already there in the system to begin with and belonged on the commercial banks’ asset side of the balance sheet. In other words, the commercial banks had already financed the US Treasury bond. Through the process of QE, the Fed now purchases the US Treasury bond from the commercial bank, which then becomes part of the Fed’s assets. In return, the Fed credits the equivalent dollar to the bank’s reserves.

Simply put, QE increases both the Fed’s assets and liabilities, or “ bank reserves” in this case. And an increase in “ bank reserves” is a sign of healthy financial conditions. When there are ample “reserves” in the system, banks will be able to easily facilitate overnight transactions and settlements in the repo market. They will also be able to absorb high quality bonds.

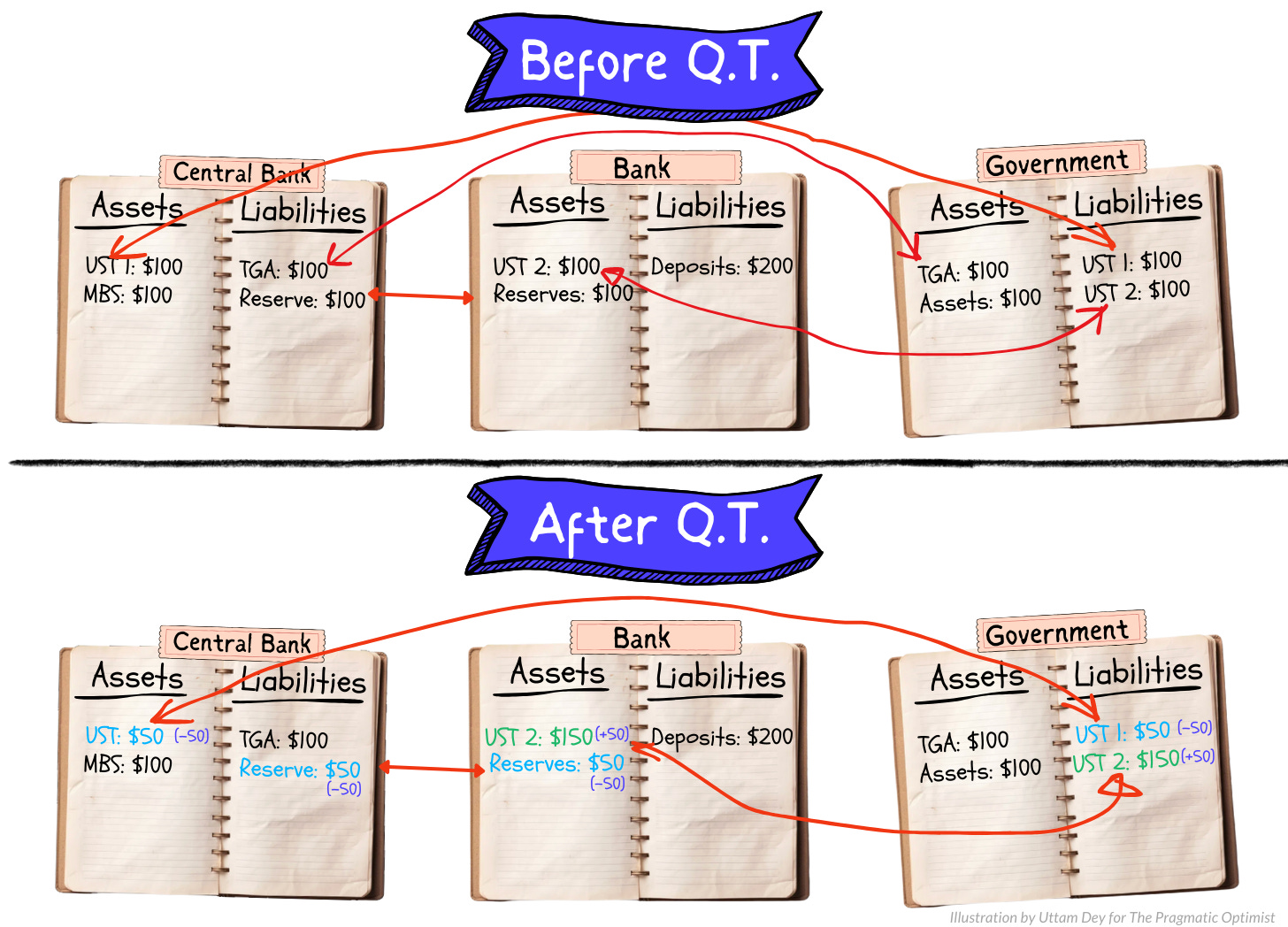

A visual demonstration of how QE creates reserves & not real-economy money

The illustration below depicts how QE simply creates “reserves” which is financial-economy money and do not create any real-economy money in the process. Also the Fed would ONLY purchase USTs (US Treasury bonds) and MBSs (Mortgage-backed securities), that commercial banks already own.

The Government’s balance sheet (before and after QE)

Before QE: The government had $200 in assets and $200 in liabilities. Out of the $200 in liabilities, $100 of US Treasury bonds are held at the Fed and the remaining $100 is held at the commercial bank.

After QE: The government still has $200 in assets and $200 in liabilities. Now, out of the $200 in liabilities, $150 of bonds are held at the Fed and $50 is held at the commercial bank. (No new debt has been issued)

The commercial bank’s balance sheet (before and after QE)

Before QE: The bank had $200 in assets and $200 in liabilities. The $200 in liabilities consist of deposits. Out of $200 in assets, $100 are held at reserves at the Fed, and the remaining $100 are US Treasury bonds.

After QE: The bank still has $200 in assets and $200 in liabilities. Nothing has changed on the liability side. On the asset side, the bank now holds $50 of US Treasury bonds (while the remaining $50 of USTs have been purchased by the Fed) and $150 of reserves (the Fed has created $50 of reserves for buying $50 in USTs).

The Fed’s balance sheet (before and after QE)

Before QE: The Fed had $200 in assets and $200 in liabilities. Out of $200 in assets, it held $100 in USTs and the remaining $100 in MBS. Out of $200 in liabilities, it held $100 in bank reserves and $100 of Treasury checking account balance.

After QE: The Fed now holds $250 in assets and $250 in liabilities. The Fed has expanded its balance sheet by expanding its “reserves:. Now, out of the $250 in assets, it holds $150 in USTs (the Fed has purchased $50 of USTs from commercial banks) and $100 in MBS. On the liabilities side, the Fed now holds $150 in reserves (The Fed has created $50 in reserves after purchasing $50 in USTs from commercial banks) and $100 in Treasury checking account balance.

Net Result: In the process of QE, the Fed’s balance sheet expands and “reserves” are created. This makes no difference to the commercial bank’s ability to create credit. Whether a bank can lend more is determined by the amount of regulatory capital it has to back new lending. During periods of QE, the yields on the longer maturity US Treasury bonds go down as the demand is high. This creates a more accommodative monetary policy, where the cost of borrowing is reduced at both the short end (through lowering short term interest rates, i.e. The Fed funds rate) and long end (through QE) As a result, investors often pivot to securities that are higher up in the risk spectrum. This can create asset price inflation, as riskier assets are bid up in an environment where the Fed is accommodating the monetary condition by purchasing US Treasury bonds and keeping yields low.

The mechanics works in the exact opposite fashion when the Fed decides to reverse QE.

What happens when the Fed “destroys” reserves?

Just like the Fed “prints” reserves, it also “destroys” or drains bank reserves, by reducing the size of its balance sheet.

!!!Enter Quantitative Tightening!!!

Here are the tightening stats since Quantitative Tightening started in 2022:

The Fed has cut it balance sheet size by $815B since June 2022. Today the Fed’s assets stand at $8.02T , from a high of $8.9T in May 2022.

Out of the $8.02T in assets, $4.9T is in US Treasury bonds and $2.6T in Mortgage-backed securities.

In total, the Fed has been able to reduce its asset size by 10% since its high in May 2022.

In order to get back to the pre-pandemic level of its asset size, the Fed has to shed an additional $4T. If it continues to reduce its holdings by $1T per year, which is approximately $83B of assets rolled every month, it will be able to accomplish the task in by 2027.

❓❓❓The bigger question is: Can it actually reduce its balance sheet to pre-pandemic levels without causing a banking crisis?

Let’s find out!!

When the Fed reduces its bond holdings, it drains/destroys “reserves” from the banking system. Bank reserves are money that commercial banks park at the Fed to earn an interest on excess reserves (IOER set at short term Fed funds rate). Bank use these bank reserves to settle transactions and lubricate the biggest funding mechanism, otherwise known as the repo market.

When the Fed starts to drain bank reserves by selling the bonds (it purchased during QE), it is a matter of time before banks and the repo market gets de-stabilized (as was the case in 2019 repo crisis). During QT, the commercial banks (private sector in general) have to accommodate more bonds (that are issued by the government) with fewer supply of reserves. As the demand for long-maturity US Treasury bonds dry up (as the Fed rolls its maturing bonds from the balance sheet and not re-investing its principle), the yields on the long maturity US Treasury climb higher. This naturally tightens monetary policy as rates go higher on the short end (if the Fed chooses to raises short term Fed funds rate) and the long end (through QT). Investors shift away from high risk spectrum assets such as equities to safer, higher yielding assets like the US Treasury bonds.

In the illustration above, I have demonstrated how Quantitative Tightening shrinks the balance sheet of the Fed as it rolls its maturing bonds from its balance sheet. This results in a net loss of reserves on the liabilities side, which is reflected on the commercial bank’s asset side. As the government issues bonds, the commercial banks need to absorb the bond issuance when their reserves are falling.

Please note that while QT has shrunk Fed’s balance sheet by 10% to $8.05T, The Fed’s liabilities stand at $7.98T. Out of the $7.98T in Fed’s liabilities, bank reserves stand at $3.2T (from a high of $4.18T in 2022). During the QE that started during Covid, we saw that the Fed’s assets doubled. In the meanwhile, the bank reserves also doubled.

Most analysts put the minimum in between $2T and $2.5T for bank reserves. This means, we can afford to lose around $1T more in bank reserves (through QT), before there is a serious liquidity crisis in the market.

Therefore, it is absurd to believe that the Fed would be able to bring down the size of its balance sheet by another $4T to its pre-pandemic level without severely depressing bank reserves, which will surely create a repo crisis similar to September 2019, or perhaps even worse.

Maintaining the availability of reserves and reverse repo is a critical function of the Federal Reserve (as per regulations post GFC). If it decided to change pricing or intentionally reduce the size of these facilities, the financial system could face serious hiccups.

In the next section of “The Fed is broke” edition, I will talk about the state of US liquidity and the future direction of liquidity in an environment where interest rates are high and the Fed is continuing to trim its balance sheet. I will then delve into the role negative equity on the Fed’s balance sheet can play to create to unleash money printing, which could prove to be disastrous for the US economy. I will also scope possible remedies the Fed can take to reverse such a scenario, within the current regulatory landscape.

Have a great week!!

Amrita 👋🏽👋🏽

Great coverage for a great start on Substack, you rock, keep it rocking!

Have a great week!

Amrita, congrats on your first subscriber milestone with many more to come as your compelling content has 10K iterations written all over it!

Thanks for including me in your journey. Keep it coming.

David

Quality Value Investing