“Don’t bet against America”- Are we entering a prolonged productivity boom?

The US sees 3 quarters of productivity growth up 3.2% YoY. Now, it needs to ensure strong employment, growing fixed invests & a stable supply side to spearhead with AI to unlock productivity gains.

Welcome back to another edition of The Monday Macro.

As part of the “Don’t bet against America” series, today’s post will explore whether the US economy is ready to enter a new period of prolonged productivity boom.

You see, productivity growth has been the primary engine of US economic power and prosperity since World War 2. And while productivity growth has sputtered over the last 15 years, there are renewed signs of optimism once again.

So, without further delay, let’s grab a coffee ☕ and a muffin and dive right in 🧁

««Monday Macro- The 2-minute version»»

The US economy is seeing productivity grow for three straight quarters, now up 2.6% YoY for 2023. This is the first time, since the 1990’s, that the US is seeing productivity growth of this magnitude. So, naturally there is cause for optimism.

But why does it matter: Productivity growth is the engine behind the power and prosperity of the US economy. In fact, the US economy needs a productivity boom now more than ever, as the US population ages and the ratio of non-workers to workers grows.

It’s not just about technological innovation: If you look to the 1980’s, computers had been around, but technology had not yet generated big productivity gains. It was only in the 1990’s that productivity boomed, thanks to falling unemployment, which led to strong consumer demand, which powered business decisions to invest in innovation & technology. Plus, the US economy was shielded from major supply-side inflationary shocks, which allowed the Fed to keep monetary policy loose, while the productivity cycle boomed.

Do the macroeconomic stars line up today? While there are signs of optimism, there still needs to be work done to further align the forces to set the foundation for long-term productivity gains. Here are the most important questions to ask:

Will the US be able to sustain full employment: While the labor market is still strong, there are signs of growing weakness as companies lay off workers in order to protect their margins, while investing in technologies to drive automation and increase operational efficiencies.

Where does AI fit in? Meanwhile, concerns about job security have risen, as Klarna implements an AI assistant that now handles the workload of 700 staff members, while Cognition AI released their “AI software engineer” called Devin who has successfully passed engineering interviews and completed jobs on Upwork.

An important distinction between automation & innovation: However, the optimistic signal right now is a boom in new business formations, which should create new jobs and lift up productivity, as cost of experimentation goes down.

A manufacturing boom with its nuances: Manufacturing spending is on the rise, especially with the CHIPS ACT driving a capex boom in AI. However, manufacturing output has not yet risen. That could be explained by the fact that factory construction takes a long time. Meanwhile, there is a growing divide between leading and lagging indicators, which underlines the current weaknesses in the industrial policy.

Supply-side shocks will be the biggest challenge: While Covid related supply-chain shocks have mostly dissipated, this decade will bring about the challenges that arise from a transition to net-zero emissions and reshoring activities as geopolitical tensions rise.

An imperative for businesses and policymakers to work together: The productivity story thus far has been of haves and have nots. While creative destruction is admittedly a part of innovation, it creates tremendous short-term pain, as people lose jobs and industries get disrupted. In a world where AI may automate several aspects of existing jobs, businesses need to provide the foundation for their employees to continuously upskill, so they can transition to more productive and higher-paying jobs. This is more easily said, than done, however.

🎥Let’s set the stage: Is productivity growth back?

The US economy is experiencing a rise in productivity growth. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data, labor productivity increased 3.2% in Q4 2023. It is now growing for three straight quarters and for the full year of 2023, is up 2.6%. For context, labor productivity grew on average between 1.1-1.4% between 2010-2020.

Naturally, a gain of this magnitude therefore is reason for optimism.

But before we get any deeper, let’s quickly turn to the basics and make sure we are on the same page as to what really is labor force productivity and why we should care.

In simple terms, productivity is the measure of output relative to input. Or, more specifically, how much output (widgets, meals, spreadsheets, computation) one person can complete in an hour.

However, measuring just how productive workers are has its set of limitations. Especially, when it comes to accounting for rapid technological progress or informal working hours. Regardless, this is still the most widely used metric to track progress in productivity.

But, the main reason we care about productivity growth is because it is the most consequential determinant of long-term economic growth. Rising prosperity, a higher standard of living can only come from productivity growth. In fact, in the long run, productivity growth and real wages are closely, if not perfectly linked.

Per a McKinsey study, should the US economy grow at an average productivity growth rate of 2.2% annually between now until 2030 (average productivity growth rate between 1948 to 2019) , as compared to the weaker 1.1-1.4% growth rate between 2010-2019, it could unlock $10T of economic output.

Now, that is a lot of jobs, wealth and prosperity for every household in the US, if distributed fairly. In fact, the US economy needs a productivity boom now more than ever.

As the US population ages, the ratio of non-workers to workers grows. This means that productivity growth in the remaining workforce will be essential to sustain output and meet the needs of the population.

Productivity growth will also keep inflation anchored, by reducing the amount of labor, capital and raw materials needed to produce a given amount of output.

At the same time, human beings have always been exceptional at increasing the size of the economic pie by inventing new areas of work and building businesses at a much faster rate than machines have automated existing tasks.

💡💡💡Think: Digital Marketing. A career I was in for over 5 years when I was in Silicon Valley, helping businesses build their go-to-market strategies. When I went to college in 2008, “digital marketing” did not exist as a career. Yet, when I graduated in 2011, digital marketing was quickly becoming a sought-after career, as mobile and cloud industries spearheaded, opening up an array of job opportunities that previously did not exist, with people upskilling in order to move to higher-paying and more productive jobs. Today digital marketing is worth a trillion dollars!

➡️So, the question of the hour: Is the productivity boom we are experiencing just a one-off growth spurt, or is it here to stay? Let’s find out.

Productivity is not just about demographics and technological innovation. Macroeconomic forces play a key role too.

Over the last year, there is a new gospel coming out of Silicon Valley, major business conferences and earnings calls with investors that Artificial Intelligence is about to make workers way more productive. There is no doubt that technological innovation, such as AI, is capable of boosting productivity growth.

However, in order to ensure that technological innovation, such as AI actually drives long-term productivity growth, we need the underlying foundation of a macroeconomic environment that supports 1) full employment, 2) growing fixed investments and 3) stable and secure supply chain.

🤔🤔Think about it: By the end of 1980’s, computers had been around for decades, but had not yet generated big gains to productivity. In 1987, the economist Robert Solow famously coined the term “productivity paradox”, where you would see the computer age everywhere, except in the productivity statistics. That only changed in the 1990’s, when semiconductor manufacturing improved and computers became cheaper. Coupled with strong aggregate demand from an economy at near full employment levels, businesses had the incentive to continue to invest in information technology to innovate their products and solutions. This in turn helped productivity to boom.

The last time productivity growth was this strong was back in the 1990’s.

has written this awesome post where he draws parallels between the 1990’s productivity boom and compares the underlying macroeconomic conditions to today’s environment.Taking inspiration from Noah’s work, let’s quickly understand why the alignment of these 3 macroeconomic forces are critical to ensuring long-term productivity growth by taking the 1990’s as an example.

➡️Take the first macroeconomic force: employment. After the Fed successfully engineered a soft landing in 1994, the US economy continued to experience a period of falling unemployment, dropping to below 4% until the end of 1990’s and before the 2000 recession. See, when employment growth is strong, it means people have access to higher paying and more productive jobs. This in turn leads to higher wages and therefore higher consumer demand. When consumer demand rises, businesses have a valid reason to invest in innovation and technology, in order to increase the size of their respective production capacities, in order to meet growing demand.

➡️This brings me to the second macroeconomic force: fixed investments. The idea is that as long as consumer demand remains robust and businesses continue to expand their production capacities to meet the additional demand, inflation will be more or less anchored, while productivity booms. During the 1990’s, investment grew in areas such as computer equipment, software, research & development, telecommunications and more. At the same time, the federal government was driving subsidies and coordinating research and development in semiconductors. In 1996, the Telecommunications Act was passed, in order to promote competition, reduce regulation, secure lower prices and encourage the rapid development of new telecommunications technologies for American consumers.

➡️Finally, to the third macroeconomic force, the US economy was fairly shielded against major supply-side inflationary shocks. Energy prices were calm, housing services were rising modestly. In fact, if you think about it, had the US economy been subject to supply-chain constraints during this period of time, it would have been really difficult, perhaps practically impossible to replicate this magnitude of a productivity boom, as the cost of raw materials and other inputs would have continued to put upward pressure on prices. In that case, the Fed would not have been able to keep monetary policy loose, like it did, which would have weighed down on consumers and businesses by forcing them to cut down spending with increasing borrowing costs. By now, we know that when consumer demand falls, business investment declines, which leads to fewer new jobs added to the economy. Result? The productivity cycle breaks.

But that did not happen in the 1990’s. The Fed kept monetary policy loose, thus allowing productivity to boom as long as it could. Even when the unemployment rate fell to its lowest ever point, the Fed could still justify loose monetary policy, as inflation was well anchored, thanks to booming productivity. Makes sense.

(Of course, there were indirect consequences of irrational exuberance in the equities market, which followed the 2000 dot-com bubble and burst. But that is a separate topic, which I am not going to get into in this post).

Are all the stars aligned for productivity to boom this decade?

I wish there was a simple yes or no answer to this question. But the truth is often more nuanced. And as a result, I will put on my “Pragmatic Optimist” hat 👒👒to assess the current situation, where we are heading and the challenges that await us in as much of an objective way as possible. So, let’s get started.

➡️ Will the US economy be able to support full employment conditions in this decade?

The US economy saw one of the fastest recoveries in growth and employment post Covid, thanks to a highly accommodative Fed and an expansive fiscal policy. Although the US labor market has cooled from its peak, where there were 2 jobs per unemployed individual in 2022 to its current level of 1.4 jobs per unemployed individual, the ratio is still at an elevated level.

However, there appears to be cracks forming with the growing discrepancies in the numbers reported by BLS and the household survey. At the same time, there is an uptick in Americans’ fear about their job security, according to polling by Morning Consult, which could be partially explained by the sheer magnitude of high-profile companies laying off workers.

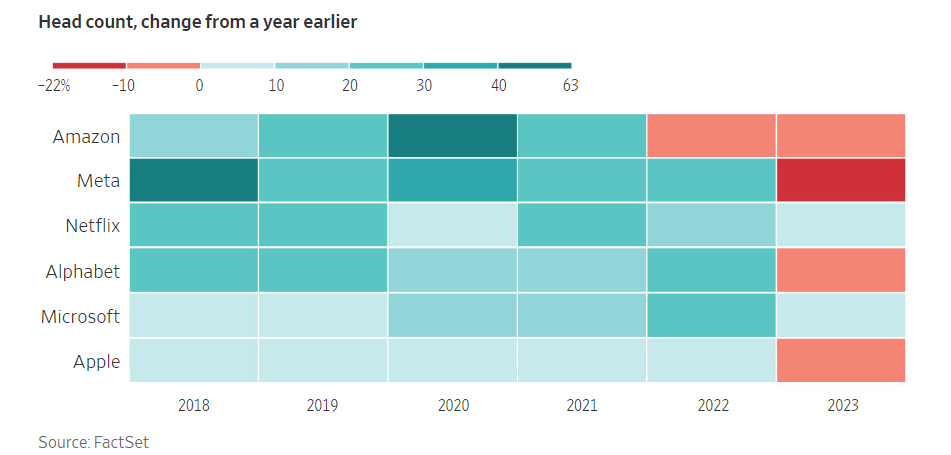

There is no denying that corporate America is serious about cutting costs this year. In January, U.S. companies announced 82,307 job cuts, more than double the number in December. Downsizing has rippled across the tech industry, as companies followed the lead of Meta’s META 0.00%↑ 2023 cuts, which many analysts credited with helping the social media giant rebound from a rough 2022. Since the beginning of 2024, Amazon AMZN 0.00%↑, Alphabet GOOG 0.00%↑, Microsoft MSFT 0.00%↑ and Cisco CSCO 0.00%↑, among others, have announced staffing reductions.

This has resulted in lower quit rates, as companies are offering new hires less-generous pay and flexibility than they did a year or two ago, data from job boards suggest.

For example, according to wage-tracking data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, people who switched jobs in August 2022 were rewarded 8.5% pay bump for making the move, around 3 percentage points more than those who stayed in their jobs. By last month, the average raise that came with switching jobs was 5.3%, compared with 4.7% for workers who stayed put.

However, lower quit rates are often associated with improving productivity. The idea is the longer you stay in a job, the better you get. The challenge now is to sustain a full employment economy, so that those workers aren’t thrown back off the job by unemployment. After all, a conversation on employment is not complete without bringing AI 🤖 into the picture.

So far, while the total number of jobs directly lost to generative AI remains low, some of these companies have linked cuts to productivity-boosting technologies, such as machine learning and other AI applications, which they continue to invest in.

Take Klarna for example. It is a fintech company that provides online financial services. It partnered with OpenAI to implement an AI assistant that is now handling the workload of 700 full time staff members, managing two-thirds of customer service chats and is expected to increase profits by $40M in 2024, as per the company statement. The management further added that the chatbot's efficiency has resulted in fewer errors, a 25% decrease in repeat inquiries and reduced average conversation times from 11 to 2 minutes. The company, after laying off 10% of its workforce last year in May, have instituted a hiring freeze.

At the same time, a couple of weeks ago, Cognition AI introduced Devin, who they call “the first AI software engineer” which has successfully passed engineering interviews from leading AI companies and has already completed real jobs on Upwork. At the moment, Devin is spreading a lot of fear about job security.

Not to mention, this paper, where scientists asked thousands of AI experts when they thought certain jobs would be automated. They asked in 2022 and again in 2023, to see how their predictions changed. The answer: a lot.

Experts think within a decade, AI will author NYT best-sellers, write top pop songs, fold laundry, and more. And since these timelines are compressing now, we can imagine they will compress further.

So, with all of the above, is it natural that people are increasingly concerned about what the future of work might look like. When will AI take my job? What kind of jobs will be available in the age of AI? Will they be well paid jobs? What will productivity look like in the era of AI?

(Note: And since AI and the future of work is such an important area of discussion, when talking about productivity, I have decided to write a Part 3 to the “Don’t bet against America” series (which was originally not intended), where I will dive deeper into the topic.)

But for now, I will leave you with an optimistic signal 🌈🌈, when it comes to the promise of the US economy being able to sustain full or near-full employment in this decade. The signal is a boom in new business formations, as you can see below. This is important since the slowing pace of business dynamism and lack of new business formations in the 2000’s is one of the reasons behind the sluggish growth in productivity during that period, particularly after 2005.

I believe that the rise in business formation suggests that people are willing to take on additional risk, and that is important in lifting productivity. Not to mention, this also indicates that the underlying technological innovation of AI has already started to reduce the cost of experimentation that allows individuals as much as companies to achieve more with less.

Starting a company and finding product-market-fit can be achieved now with fewer resources with the help of copilots and AI-powered products. This is similar to how the introduction of cloud computing services by Amazon AWS is seen by many practitioners as a defining moment that dramatically lowered the initial cost of starting Internet and web-based startups.

➡️The US is experiencing a manufacturing boom. But, it has its nuances.

A strong labor market and consumer demand has ushered in a surge in construction spending for manufacturing facilities. Real manufacturing construction spending has doubled since the end of 2021 as the policy environment for manufacturing construction such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and CHIPS Act each provided direct funding and tax incentives for public and private manufacturing construction.

Here’s manufacturing construction spending as a percent of GDP, which goes back a few more years. This too, is telling the same story.

Within real construction spending on manufacturing, most of the growth has been driven by computer, electronics, and electrical manufacturing. Since the beginning of 2022, real spending on construction for that specific type of manufacturing has nearly quadrupled.

However, when we dig one layer deeper, we see that manufacturing output hasn’t risen at all. One explanation could be that factory construction simply takes a long time and we would have to wait a couple of years before they start pumping out computer chips, cars and other manufactured goods to be reflected in the output. The second, more pessimistic explanation could be bureaucratic hurdles and onerous contracting requirements.

However, we may be starting to see an increase in manufacturing output sooner rather than later as the S&P Global US Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index points to strengthening durable goods orders. At the same time, the US is importing more capital goods, which has increased at an annual rate of 9.6% over the past 6 months. Remember imported capital goods are used for domestic production.

On the other hand, growth in real investments is sizable lagging in other sectors, thus creating a “mixed picture” when you look at the state of fixed investments as a whole. This is what

had to say in regards to the current landscape of fixed investments, which I fully echo with.“The situation on investment is mixed. While growth in real investment in some areas, most notably manufacturing structures, is strong (supported by programs such as CHIPS and IRA), investment in other areas is slowing noticeably. Of note, multifamily housing permits have declined over the past few quarters and real private research and development has actually shrunk over the past couple of quarters. In sectors where fiscal policy is not providing direct support, we see investment in further retreat. Even as the effects of monetary tightening are not as readily visible and identifiable with respect to consumption, it has had a more identifiably restrictive effect with respect to fixed investment outcomes.”

The way that I see it is that we are moving away from the notion of efficient and self-correcting markets, to an age in which the public sector will do more nudging, or “marketcrafting” to ensure economically and politically stable outcomes. The growing divergence in productivity between the leading relative to lagging sectors and the resulting social and wealth inequality is one such example, where it demonstrates the urgency behind a robust US industrial policy, which would require concerted effort by business leaders and policymakers to drive desired outcomes. Else, we could end up in a scenario, where even if stimulus dollars get rolled out quickly to fund certain initiatives, there may not be enough skilled workers to fill positions.

➡️Shielding the US economy from supply-side inflationary shocks look to be the most challenging

While Covid related supply-chain constraints have mostly dissipated, I believe the largest threats to the future supply -side inflationary shocks will be driven by 1) transition to net-zero emissions and 2) reshoring activities because of increasing geopolitical tensions.

Over the past 30 years, energy costs have remained relatively stable, even as economic output more than doubled. As firms now embark on the transition to net-zero emissions, the rising cost of energy could turn into a headwind for productivity. At the same time, I will also note that the road to net zero will also present new opportunities to bolster productivity growth, for example, through decreased volatility of energy costs and for job creation in manufacturing and construction.

As for deglobalization, the narrative came front and center during Covid, when companies and nations around the world realized the vulnerabilities of their supply chains, with the risk being concentrated amongst a few trading partners. Plus, over the last four years, we have seen geopolitical tensions rise, with ongoing wars between Russia and Ukraine and Israel & Gaza. While we have seen numerous companies, including Apple AAPL 0.00%↑, Nike NKE 0.00%↑, Microsoft, Intel INTC 0.00%↑, Dell DELL 0.00%↑ , among others, take initiatives to de-risk their supply chains while reshoring to “friendlier” borders, I expect that nations and businesses will continue to monitor and assess the resilience of their supply chains in order to ensure access to raw materials and other resources necessary for production as the world becomes more multipolar.

🪢Tying it all together…

In Part 1 of the “Don’t bet against America” series, I explored how the US came to become the center of the new world order after WW2, given its sheer strength across all domains.

Over the last 75 years of its world dominance, it has gone through multiple credit booms and busts, as well as game changing innovation cycles that has allowed it to prosper. While the US economy has declined in relative strength during the course of its world domination when it comes to the quality of education, competitiveness and share of world trade, it still leads the rest of the world when it comes to its robust pace of technological innovation, which is driving strength in its financial markets, ultimately ensuring the reserve status of the US dollar as well as its military prowess.

However, in order to continue to maintain its stronghold in the world order, the US now needs a prolonged period of productivity boom. While there are signs of optimism, with three straight quarters of productivity gains along with improving signs of the three macroeconomic forces of full employment, fixed investment and stable supply-chain aligning better than before, there still needs to be work done to set the foundation.

The biggest challenge in my view is that the US productivity has been a story of haves and have-nots. While technological innovation has lifted productivity in some sectors, its benefits have not been fully captured. Meanwhile, another concerning area for me is that the link between productivity growth and real wages have weakened, where real wages are growing much more slowly than the overall productivity growth.

There is no denying that creative destruction is a natural progress of innovation, where companies that fail to embrace new technologies get disrupted. Think: Blockbuster, Radio Shack, Toys R Us, Xerox, Kodak, Nokia and many more. While creative destruction ultimately leads to a more effective reallocation of resources such as capital and labor to more productive parts of the economy, there is tremendous short-term pain associated when companies and industries get disrupted. People lose their jobs, consumer confidence goes down and there is a general sentiment of anxiety. Creative destruction is also naturally deflationary. However, this is not the “good” disinflation from productivity gains, but the “bad” deflation from falling consumer demand.

As a result, there is an urgency now more than ever, for concerted efforts between the business leaders and policymakers to spend resources in building a resilient workforce for the future. In a world where several aspects of our existing job requirements may become automated because of AI, businesses need to provide the foundation for their employees to continuously upskill, so they can transition to more productive and higher-paying jobs. I admit, this is more easily said, than done, as adjustment does not come easy for human beings and companies, as economic models would usually have us believe.

Let’s admit it, there are lots of unknown unknowns in the path ahead of us as the US economy successfully steers ahead. Whether the US economy embarks on a prolonged period of productivity boom is still uncertain. And while I have painted this post with broad brushstrokes, I want to end on a note of optimism. And as long as we are pragmatic about our optimism, we take bold steps, experiment, learn, fail and relearn. That is after all the American spirit, that embodies the spirit of innovation, progress and resilience that drives the United States forward.

Onwards and upwards!!! 🗽🗽🗽

Stay tuned for Part 3, where I will dive into my three predictions for what the future of work and productivity look like in the AI era.

Here’s an amazing video by

that I have to leave you all with as we end this post, in case you have lost faith in the West.That’s all for today, folks. Hope you found this post useful.

Please leave your thoughts in the comments section below.

Amrita 👋🏼👋🏼

That was a fun read. My only criticism is that that emoji was clearly a cupcake and not a muffin.

I usually don't repeat "Never bet against America" but in the current macroeconomic environment, which one country is a big winner? The US, by far.