Risk a banking crisis or reignite inflation? The Fed's worst dilemma is here.

The Fed is reluctant to cut rates as the US economy continues to remain resilient. However, the longer rates remain high, credit risks grow, with the US regional banks at the line of fire.

Welcome back everyone to another edition of The Monday Macro (on Tuesday).

I am sorry for the delay in publishing the post, as it took me a while to condense a topic that I am very passionate about in an easy-to-understand, jargon-free post, that will be accessible to you all.

In today’s post, we talk about the Fed’s dilemma: To cut or not to cut rates? That is the question that will determine whether we risk a banking contagion or reignite the flames of inflation once again.

We are going to go down a rabbit hole in order to understand how we have arrived at this point and what are the risks that we face moving forward.

So, let’s grab a coffee and a muffin and dive right in. ☕🧁

««Monday Macro- The 2-minute version»»

The Fed’s dreaded dilemma is here. To cut rates or not to cut rates? On one hand, the Fed is reluctant to cut rates as the US economy remains resilient. On the other hand, the longer rates remain high, the greater the risks grow in the banking system, with the regional banks facing the full brunt of it.

But first: How did the the US economy remain resilient thus far, even when the Fed was raising rates and performing Quantitative Tightening (QT)? The answer lies in the $2.5T worth of pent-up liquidity in Money Market Funds that had built up in the Fed’s Reverse Repo Facility (RRP), which played a pivotal role in absorbing new shorter-dated Treasury debt issuance, thus keeping bank reserves mostly intact.

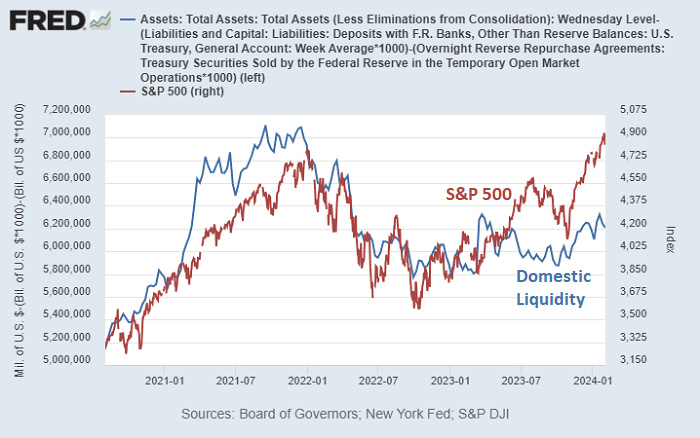

Result? The liquidity in the US banking system remained steady (a surprise to many). This kept the US economy resilient and the stock market roaring.

And now what? The mechanics of the monetary plumbing that allowed the US liquidity to remain resilient, is now going to turn into a headwind.

The depleting RRP barrel: Once RRP’s are drained out, bank reserves will have to come back into the picture to absorb new Treasury debt issuance (like it was originally intended to, during QT). This will worsen liquidity conditions from current levels, especially if the Fed doesn’t slow down the pace or pause its QT program.

Big banks vs. small banks: Big banks are in significantly better financial health compared to small banks, when looking at cash levels relative to their assets. This means, credit availability is likely going to remain more accessible to larger companies than smaller companies, and small banks continue to be at risk of solvency issues and consolidation.

Cutting off the lifeline support: 2 weeks ago, the Fed announced that it intends to retire the Bank Term Funding Program (BFTP) by March 11, a liquidity program that had allowed banks to borrow from the Fed at favorable conditions. While a lot of banks feasted at the BFTP facility (given the design of it), cutting off the facility will put numerous regional banks in grave liquidity danger in the coming months.

The evidence is building up: Last week, New York Community Bancorp’s share price plummeted 44% after posting a loss in its Q4 earnings, as it slashed its dividend and set aside hundreds of millions of dollars in provisions for potential bad loans in its Commercial Real Estate portfolio. Other regional banks with high exposure to CRE loans include Banks OZK and Valley National Bancorp.

Let’s set the stage!!!

As we finish the first month of 2024, the US economy continues to remain resilient. Inflation further cooled down from its peak to 2.9% in December 2023, while the labor market added 223,000 jobs, with average hourly wages growing at 4.5%, outpacing inflation and boosting US consumers' spending power. At the same time, corporate earnings continue to grow robustly, with S&P 500 earnings projected to grow 10-11% in 2024.

All of this, when the Fed has raised interest rates 11 times to 5.25-5.5% over the last 2 years in one of the most aggressive rate hiking cycles in modern history. Not only that, during this same period of time, the Fed also managed to shrink its balance sheet size from $8.9T to $7.6T. A truly wondrous achievement, I have to admit.

Yet, here we are now, where the Fed is at a major crossroads on how to drive its monetary policy moving forward. On one hand, the Fed is reluctant to start cutting rates too soon, because the US economy is resilient thus far, and loosening monetary policy (fancy term for cutting interest rates) may reignite inflationary pressures.

On the other hand, the longer interest rates remain high, the greater the credit risks grow, especially for regional banks in the US, which have a disproportionately higher exposure to more vulnerable sectors, such as Commercial Real Estate (CRE). As we saw last week, New York Community Bancorp NYCB 0.00%↑ announced a “surprise” loss driven by declining net margins and loan loss reserves rising 10x vs. estimates in provisions for potential bad loans in its CRE portfolio.

To add to the complexity, the Fed also announced two weeks ago that its “Bank Term Funding Program” (BFTP), which provided liquidity to banks and financial institutions on favorable terms post the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) collapse, will be terminated by March 11th, putting the US regional banking sector at the line of fire.

Welcome to the Fed’s dreaded dilemma!!!

But how did the US economy manage to stay resilient so far?

If you are thinking excess consumer savings and easing of supply chains, you are partly correct. But you are still missing the big picture. And by the big picture, I mean LIQUIDITY.

Let me explain.

Fair warning: we are going to get into some level of detail into how the financial plumbing works to explain liquidity, but I will try my best to explain in the simplest way.

In March 2022, the Fed had announced that it would start to reduce the size of its balance sheet by selling approximately $100B of assets (combination of US Treasury bonds and Mortgage-Backed Securities) every month, through a process called Quantitative Tightening (QT). Since then, it has reduced its balance sheet size by approximately $1.3T from its peak to its current level of $7.6T.

When the Fed performs QT, it essentially drains bank reserves, thus reducing overall liquidity in the financial system in the process.

How does that work? 🤔🤔🤔

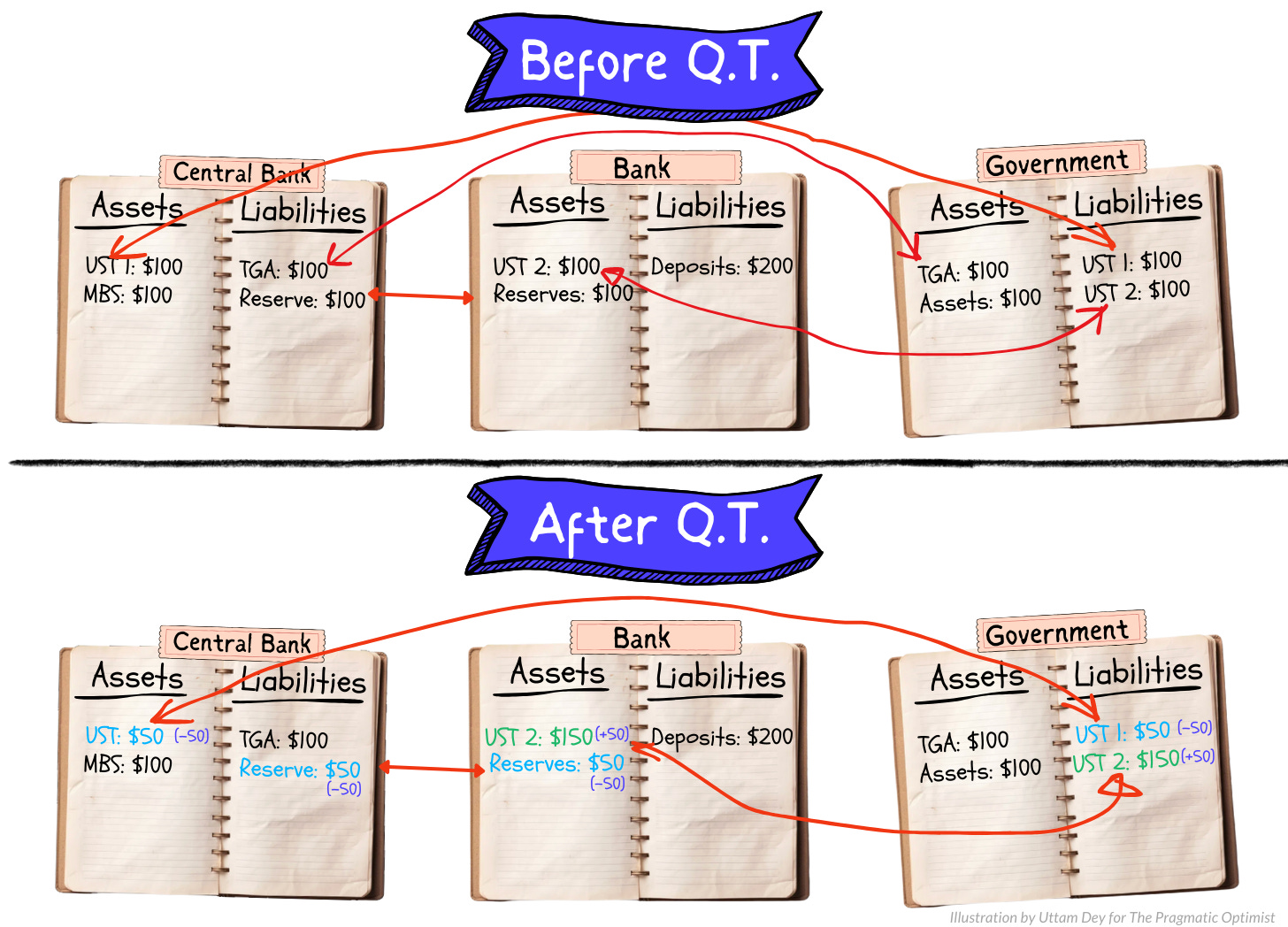

If you remember, during the Covid 19 pandemic, the Fed announced that it would perform Quantitative Easing (QE), where it would buy a combination of US Treasury bonds and Mortgage-backed securities. When the Fed performs QE, it purchases the US Treasury bond sitting on the asset side of the commercial banks, by “printing” a dollar in the bank reserves, which then becomes part of the Fed’s assets, as I have illustrated below.

An increase in “bank reserves” is a sign of healthy financial conditions because bank reserves are money for banks, which they use to transact with each other and with the Fed in order to settle transactions, buy bonds from each other and ensure the proper functioning if the biggest funding mechanism in the world- the repo market.

However, the Fed can also reverse the process of QE by destroying reserves from the system in order to drain liquidity. When the Fed performs QT, the Fed shrinks the balance sheet on both the asset and liability side as it sells off maturing bonds without reinvesting in them. As a result, bank reserves are destroyed as can be seen below.

Add government bond issuance to the mix on top of that, the banks now need to absorb it with less reserves on hand. As a result, overall liquidity in the banking system faces pressure from both the Fed and the government. This in turn forces banks to curb their lending, which ultimately results in less real economy money and an eventual slowdown in inflation and growth.

(In case you are interested, I had written a deeper dive on the mechanics of QE/QT a while back, so you can check it out.)

Now, coming back to how the US economy managed to stay so resilient, despite the Fed draining liquidity, something unique happened in this cycle that is not seen in a conventional QT.

Back in 2021, when interest rates were at 0%, Money Market Funds (MMFs) were bidding up T-bills, so much so that yields were testing negative territory, and therefore to stabilize the money market rates, the Fed proposed the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP).

An RRP is the opposite of a repo, where the bank loans to the Fed and the Fed posts a collateral, usually a US Treasury. When the short-term loan is up, the bank gets their principal back with interest. Sweet deal!! 💰💰💰

So, this encouraged MMFs to park their money at the Fed, and they did in huge sizes of up to $2.5T by December 2022.

If you are thinking, why on earth would a bank lend money to the Fed, who can self-sufficiently print money themselves, I would recommend reading

who has this excellent post, which elegantly describes the mechanics of repo and RRPs and how it allows the Fed to control the money in circulation by operating these 2 facilities.Here’s a great perspective from

which I have quoted below:In 2023, the Fed was paying over $800M in daily interest to “sterilize” $6T through its reverse repo facility and interest on reserve policy combined. Let that money out to play, and it’ll quickly turn into about $60 trillion – then you’ll see some REAL inflation.

With the huge pile of RRP sitting in the system, US Treasury Secretary, Janet Yellen, thought of something shrewd.

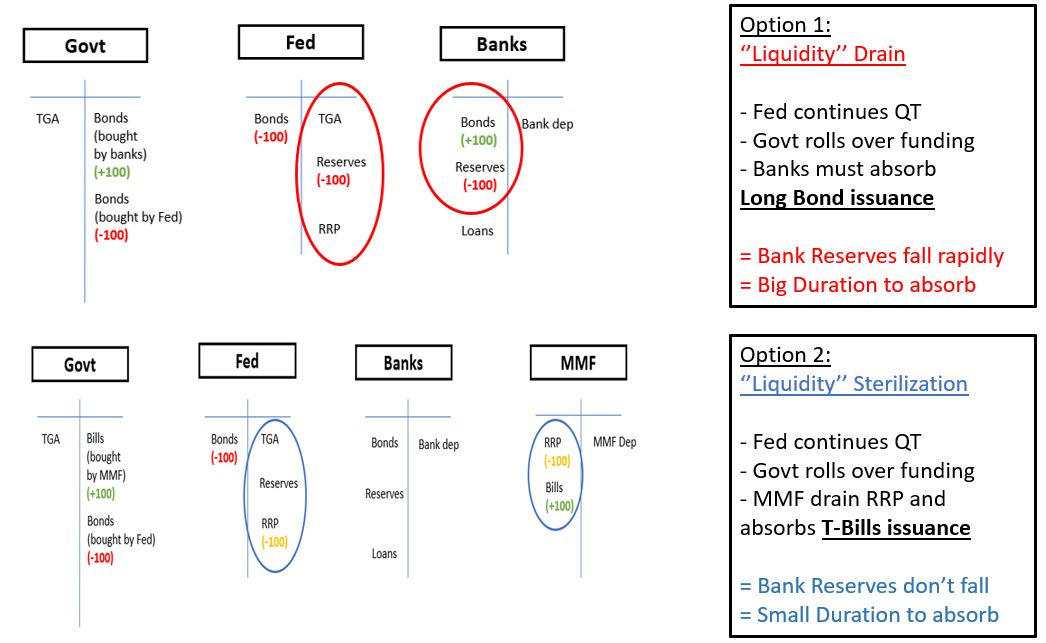

In the coming months (and ongoing), the US Treasury would issue new debt dramatically skewed towards the T-bills. Remember, T-bills have a shorter date to maturity usually of four weeks to a year, compared to T-bonds, which are longer in duration.

How would issuing shorter duration debt help keep the US economy resilient Excellent question. 💡💡💡

Remember, earlier, when I said that in 2021, the Fed had created the RRP facility, so that MMF’s can be parked there, instead of bidding up T-bills into negative yielding territory. Well, by issuing shorter duration debt (T-bills), the US Treasury used the MMFs parked in the RRP facility to absorb it, which reduced the size of the RRP facility from $2.5T to $552B, but kept the overall liquidity conditions in the financial system unchanged.

has this illustration that depicts how MMFs soaking up shorter term bill issuance leaves overall liquidity conditions unchanged. He also wrote a great post on this on this topic a month ago.Result?

➡️ The Fed was able to reduce its balance sheet from $8.9T to $7.6T.

➡️ Bank reserves fell just $0.7T, as they didn’t have to soak up higher duration risk.

➡️ Meanwhile, the US Treasury continued its borrowing spree, while draining the RRP facility, which is now down from its peak of $2,5T to $552B.

➡️ Overall liquidity in the US banking system remained unchanged.

➡️ The US economy remained resilient.

📈 Oh… and the stock market loved it.

Still don’t believe me? Look at the chart below.

So what happens now? Real Rates continue to squeeze, RRP barrel will soon be empty & Regional banks at the line of fire

Given how the Fed has navigated the economy thus far, with raising interest rates at the fastest pace and reducing the size of its balance sheet without the US economy tipping into a recession, one might ask: Why can’t this go on forever?

Well for one, the Fed funds rate at 5.25-5.5% today is significantly higher than the 6-month annualized Core PCE. The last time “real rates” (Fed funds rate - Core Inflation) were this high was back in 2007, and the economy was fundamentally different back then with significantly less leverage. The longer real rates remain at such levels, the greater the risk that the Fed commits a serious policy mistake.

At the same time, the mechanics of monetary plumbing that has allowed liquidity conditions to stay resilient in the US economy is going to prove to be a headwind.

What do I mean by that?

While the Fed’s balance sheet has not come down to its pre-pandemic level, one concern is what happens to overall liquidity once the RRP’s are drained out. At its current pace, RRP’s will most likely be drained out of the system by summer of 2023. At that time, the bank reserves which were originally meant to absorb new Treasury bond issuance would need to come back into the picture to do its job.

Result?

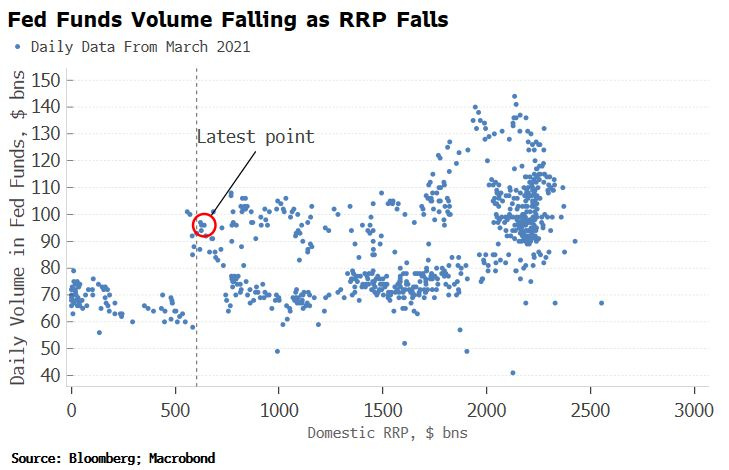

Liquidity conditions will likely worsen from current levels, especially if the Fed does not slow the pace or pause its QT program. While the Fed has mentioned that it would outline its plans for QT in the upcoming meetings, here is an interesting chart that shows that domestic RRP’s are at an interesting juncture, where historically a further drop in RRP has coincided with a drop in reserves volume, increasing the likelihood of a nearby funding flare-up/crisis, similar to what we saw in 2019 repo crisis.

At the same time, although liquidity conditions have remained resilient thus far, there are some discrepancies when you dig deeper into the data. It looks like it is the big banks that have been the primary beneficiaries in the entire process, while smaller banks continue to be vulnerable. The following chart shows the cash levels of large banks in blue and small banks in red.

You can also look at it another way. This is the same chart, but is re-denominated to be in terms of cash as a percentage of total bank assets.

Remember, large banks lend to large companies, while small banks lend to small companies. And so, credit availability is likely going to remain more accessible to larger companies than smaller companies, and small banks continue to be at risk of solvency issues and consolidation, especially the longer interest rates remain high, whereas large banks in general are in decent shape.

Last week, we saw New York Community Bancorp’s (NYCB) share price plummet 44% after posting a loss of ($260)M in its Q4 earnings, as it slashed its dividend and set aside hundreds of millions of dollars in provisions for potential bad loans in its CRE portfolio.

With interest rates as high as today, NYCB’s net margin is getting squeezed. NYCB paid an average rate of 3.62% on deposits in Q4, up from 1.93% a year ago. At the same time, NYCB’s loan growth has stalled. That is squeezing profitability with its net interest margin falling 45 basis points (0.45%) to 2.82% quarter on quarter (QoQ). That is expected to fall further in 2024. with Net interest income projected to fall as much as $300M this year.

Then there is the commercial real estate dilemma. Most banks want to reduce their exposure to this $5.8T market. As per Financial Times, among regional banks, Bank OZK and Valley National Bancorp stand out, with high exposure to CRE loans but low CRE reserve ratios, according to Morgan Stanley research. At OZK, CRE loans make up some 63% of the bank’s earning assets. More CRE write-downs will mean smaller regional banks have more firefighting to do.

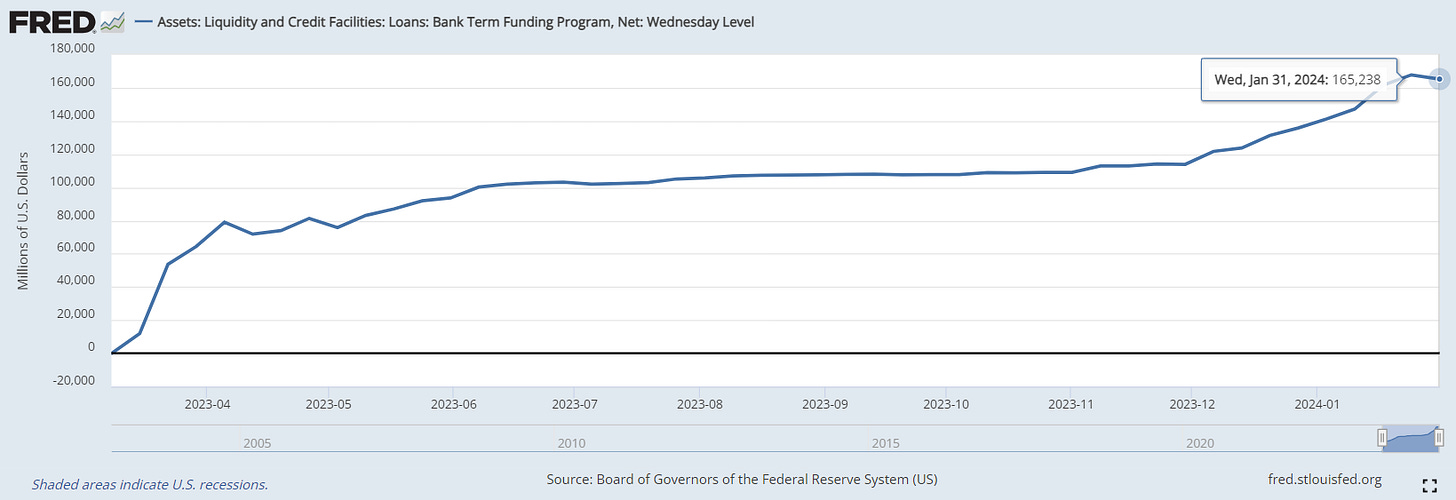

Complicating matters further, the Fed announced the closure of its Bank Term Funding Program (BFTP) two weeks ago, which has been a lifeline to regional banks after Silicon valley Bank collapsed.

How will terminating BFTP affect liquidity?

In order to answer the question, let’s do a quick primer on BFTP. BFTP was a program created by the Fed in March 2023, when the Fed realized that banks, especially regional banks were under-capitalized due to the crash in Treasury bond prices.

Remember what happened leading up to this...

Banks bought lots of long-term USTs in their reserves → Fed raised rates at the most aggressive past→ long-term bond prices crashed → bank reserves crashed in value → depositors threatened bank runs → Fed created BTFP to save banks

The terms of the facility were highly favorable in that Treasury bonds (that had crashed in price) were exchanged for full face value, rather than market value, lower interest rates than available in the open market for borrowing, and complete secrecy to hide any banks that were having liquidity problems.

However, 2 weeks ago, the Fed imposed an interest rate floor on the BFTP loans equal to the interest rate on reserves, along with the announcement to retire the program by March 11. On one hand, while this puts an end to certain banks who had been feasting, by borrowing at the BFTP facility for a lower interest rate and depositing that money as reserves at the Fed at a higher interest rate, on the other hand, this puts numerous small regional banks in grave danger as they were genuinely reliant on the BFTP as their only source of credit.

Think about it:

Let’s say a bank had an asset like a mortgage with a 4% interest rate but was paying 5% interest on its deposits, effectively losing 1% on its balance sheet. It went to the Fed and used that mortgage as collateral for a loan at the BFTP with an interest of 4.5% and used the proceeds to finance another mortgage at 6%. At first, it looks like the bank is making 1.5%, but after deducting the 1% it’s losing from the original mortgage and depositors, the bank is only clearing 0.5%.

-

With that in mind, imposing an interest rate floor on the BTFP equal to the interest rate on reserves has now spiked the cost of borrowing for the banks who are truly in trouble and were using the facility as intended.

As a result, last week, the loans from the BFTP facility went down, as the current design of the program is no longer attractive for regional banks to borrow from it.

Moving forward, the Fed will require banks to use the Discount Window instead, which would allow banks and other financial institutions to borrow from the Fed on a short-term basis in order to meet reserve requirements or address temporary shortages.

(Please note that the Discount Window is not a new facility and in the past had often played a critical role in maintaining stability in the banking system during times of financial crises.)

However, there are some key differences between BFTP and the Discount Window, as James Lavish had pointed out in his post.

Connecting all the dots together…

Liquidity leads the economy. It is stable liquidity conditions, despite the Fed reducing their balance sheet size, that contributed to the resilience of the US economy and the bullish narrative of the stock market.

However, now, we are at a critical juncture.

On one hand, Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell asked Americans to be patient as the effects of high interest rates ripple through the economy, while noting he still anticipates multiple interest rate cuts this year.

"We've said that we want to be more confident that inflation is moving down to 2%. It's not likely that this committee will reach that level of confidence in time for the March meeting, which is in seven weeks," Powell said.

Meanwhile the longer the rates remain high, the greater the risks of a liquidity event developing in the banking system.

While RRP’s still have some time left before they are fully drained out, the bigger issue at hand is the discrepancy in financial health conditions between larger and smaller banks. The longer the interest rates remain high, the higher the funding costs, which squeezes banks’ net interest margins, as we saw with the latest earnings of NYCB. Furthermore, regional banks have a deeper concentration of loan assets in commercial real estate, which is a ticking time bomb.

To complicate matters further, the expiration of the BFTP facility, which proved to be a lifeline of liquidity for smaller banks as they struggled with the duration risk of assets and customer withdrawals post the SVB collapse, can have serious repercussions for the stability of regional banks.

The truth is, that the Fed knows this already. The timely omission of the following sentence about the resilience of the US banking system could very well be foreshadowing of a repeat of a 2023 style regional banking crisis.

While many experts claim that the size of commercial real estate, particularly office real estate, is not large enough to start a wide-spread banking contagion, it is pretty obvious to me at this point that the Fed is prioritizing its fight against inflation over saving a handful of regional banks.

After all, big banks are in good shape, right? So, when the next regional bank collapses, the much awaited (hint: Yellen) “banking consolidation” will be back on the table.

Let’s do a quick polling on the next macro topic you want me to write about!!!

That’s all for today, folks. Hope you found this post useful.

Do you think the Fed is doing the right thing by waiting to cut? Are we at the cusp of seeing more banking consolidation in the coming years? Do you think the troubles of the regional banks can turn into something greater?

Please leave your thoughts in the comments section below.

Amrita 👋🏼👋🏼

Awesome post!

I'm thankful there are very intelligent people like you who can break this down for people like me who are very ignorant about it. You make it so much easier to understand.