What is the Fed’s next move? Hike rates, raise the inflation target, or do nothing at all?

The US economy is a story of acute divergences, making it increasingly hard for the Fed to deliver on its mandate of 2% inflation rate. It's going to be a bumpy ride.

««Monday Macro- The 2-minute version»»

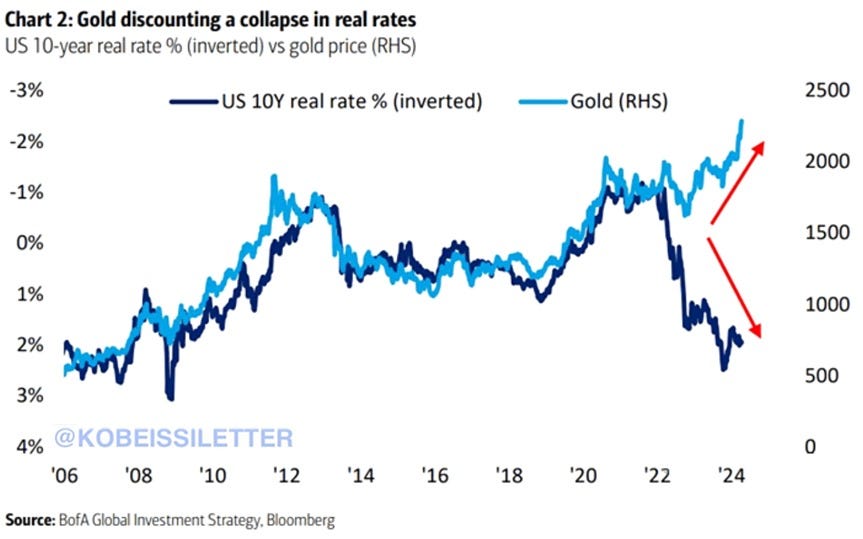

Macro Volatility has picked up lately. The 10Y US Treasury bond yield is steadily climbing, while interest rate futures are now pricing in just 2 rate cuts in 2024, lower than the Fed’s projections. Meanwhile, commodities are rallying, while gold diverges further from the 10Y US Real rate. What’s going on?

It all started with the CPI report: That’s correct. Core CPI printed on the hot side again for the third time in a row in 2024. This is even after the Fed raised rates 11 times to 5.25-5.5%, and has still not managed to slow the economy enough to reach its target inflation rate of 2.2%

But first, what is the obsession with 2% inflation? Turns out, there isn’t much science behind it after all. With its roots in New Zealand in 1989, it was not until 2012, when the Fed openly embraced the 2% inflation target. If you remember, the Fed had revisited its 2% inflation target in 2020, when it widened its range in subtle ways after a decade of sub 2% inflation.

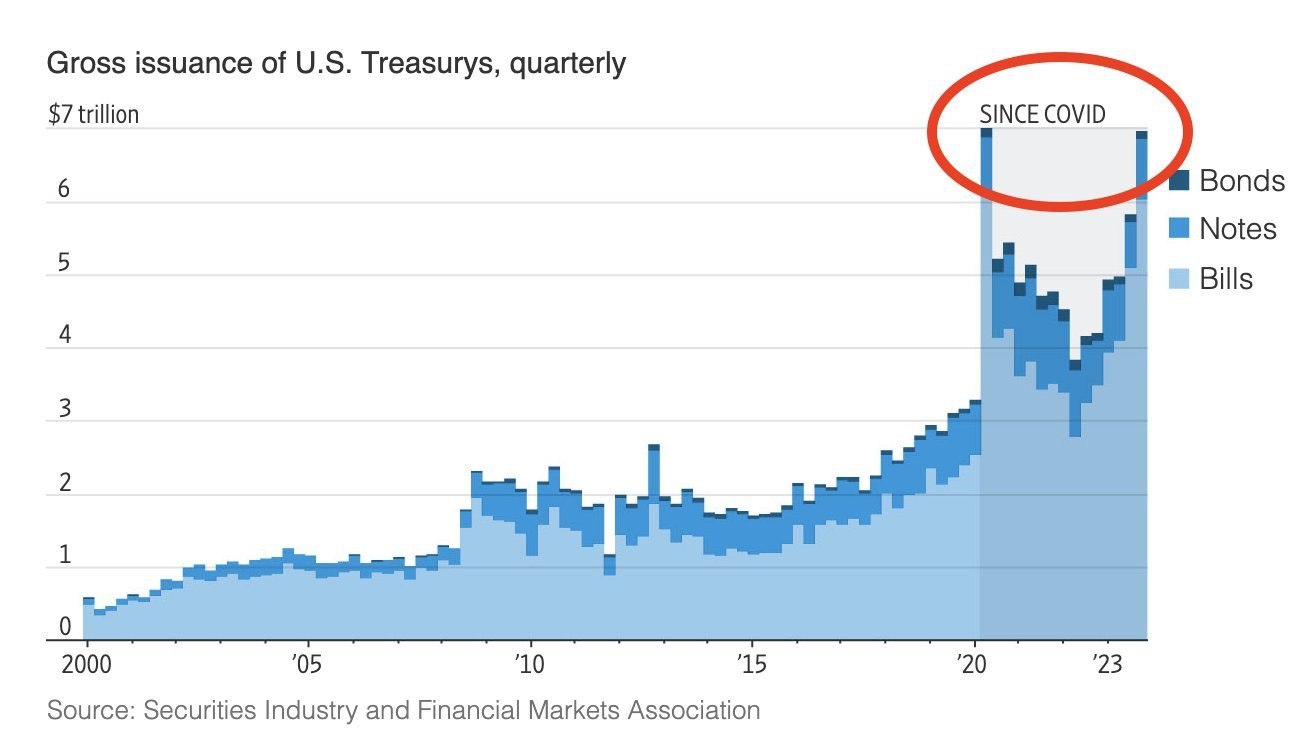

We’re in strange times: Today, the inflation expectations are rising once again, when the Fed has already raised times at its most aggressive pace in this century. Meanwhile, the US government is issuing Treasuries like we are in crisis times.

Welcome to fiscal dominance: Unlike the 2005-07 period, the main driver of inflation today is government deficits, as opposed to private sector borrowing. The most concerning part is that interest rates are not an effective monetary tool to curb fiscal-driven inflation. In fact, it further exacerbates it. Therefore, no matter how much the Fed claims that it is “data dependent”, the truth is that it has to lower rates to help fund the deficits and ensure the smooth functioning of the Treasury market.

The case for hard assets grow: Gold seems to have already sniffed out that an accommodative monetary policy to support government borrowing will likely lead to weakening of the currency and higher inflation over time, surging 17% YTD. Plus, central banks worldwide are increasing their gold holdings for 9 straight months, as they race to improve the quality of their reserves.

Productivity growth is the only beacon of hope: Meanwhile, the US economy is adding jobs at a rapid pace, as the labor market gets bigger with higher labor force participation rate, while wages remain anchored. In fact, a strong labor demand is a necessary ingredient to set the foundation for a long-term productivity growth, as it leads to higher business investment in technology and innovation to increase capacity to meet higher consumer demand.

So, what will the Fed do next? Here are 3 options.

Raise rates enough to hit that 2%target? Unlikely, in my opinion, given that long-term inflation expectations are still anchored within range. Plus, why destabilize the UST market and kill a nascent productivity boom?

Raise the inflation target? Not yet. The Fed risks losing its credibility, if it is not communicated correctly. This could disrupt inflation expectations, leading to soaring inflation premiums for borrowers, driving up government’s deficits and reducing private investment.

Do anything at all? This seems to be the wisest option to me at the moment and let the bond market do most of the work for it. Having said that, the more successful the Fed is in fighting inflation now, the more room it will have to make the right long-term moves for the U.S. economy.

Let’s set the stage!!!

Volatility is picking up, and this might be just the beginning.

Over the last 2 weeks, the 10Y US Treasury bond yield has spiked 30 basis points to 4.62%. Interest rate futures are now pricing in just 2 rate cuts by December 2024, compared to 4 months ago, when markets were pricing in 6 to 8 rate cuts in 2024. Meanwhile, the US Dollar has appreciated. Commodities are surging. And in all of this, gold is trading in a world of its own, as it diverges further and further away from the 10Y US Real rate. A strange phenomenon, or, is it really?

In this post, I will give it my best shot to connect the dots across these signals to make sense of what is driving the volatility and lay out a framework for how to think about the Fed’s monetary policy moving forward.

It all started with the CPI report.

That’s correct. Core CPI printed on the hot side again for the third time in a row in 2024. Let’s dive in.

The 3 month annualized Core CPI is now at 4.5%

The 6 month annualized Core CPI is at 3.9%

This is double the Fed’s target of 2.2%. 😨

But, it gets even uglier if you look at Super Core inflation, which the Fed refers to as the stickiest part of the inflation basket.

FYI: The Super Core inflation refers to the rising cost of goods and services, excluding food 🍲, energy 🛢️ and housing 🏡.

The 3 month Annualized Super Core CPI is at 8.2%

The 6 month Annualized Super Core CPI stands at 6.9%.

Up until now, the S&P 500 had been climbing higher and making new highs, under the assumption that the US economy would successfully engineer a soft-landing. That’s because inflation had been steadily declining since its peak of 6.6% in 2022 (Core CPI), while company earnings continued to surprise on the upside.

Yet, here we are, ironically enough, where even after the Fed raised rates 11 times to 5.25-5.5%, the US economy has still not slowed enough to reach the Fed’s target inflation rate of 2.2%. In fact, we may have temporarily ushered in a new wave of inflation growth with the loose monetary conditions that ensued towards the end of 2023, when the interest rate futures were far more optimistic than the Fed, when it came to its projections for the number of interest rate cuts in 2024.

So, now the Fed has to make a decision once again. Will it raise the inflation target, hike rates or do nothing at all?

But, before we move any further, let’s address the elephant🐘 in the room; what’s with the 2% inflation target?

What is with the 2% inflation rate? A sacred number or pure hokum

💭Did you know that when Paul Volcker left office in 1987, inflation was still above 4%?

(In case you don’t know, Paul Volcker is a renowned Fed chair known for vanquishing inflation in the 1970s and ‘80s.)

Turns out, that the 2% inflation target is indeed something of a historical accident. It has its roots in New Zealand when it passed a law in 1989 that established the independence of the country’s central bank.

In fact, it was not until 2012, when the Fed openly embraced the 2% inflation target formally, and made it part of the Fed’s practice of “forward guidance”. And if you remember, the Fed had revisited their 2% inflation target by 2020, where it widened its range in “subtle ways” after a decade of sub 2% inflation rate.

My hunch is that if the Fed were adopting an inflation target from scratch today, it would likely choose a target above 2%. A higher inflation target has the benefit of helping cushion the economy against severe recessions. But, it also comes with costs, as people and businesses would need to account for how much their current dollars would be worth in a year or so.

The truth is however, the Fed is not starting from scratch. The 2% inflation target, which was formalized in 2012 has had some real benefits. People expected inflation around 2%, and for the most part that’s what they got.

And whatever considerations led policy makers to conclude that 2% was the right number in the 2010’s, I strongly believe that an inflation target should be based on longer-term considerations.

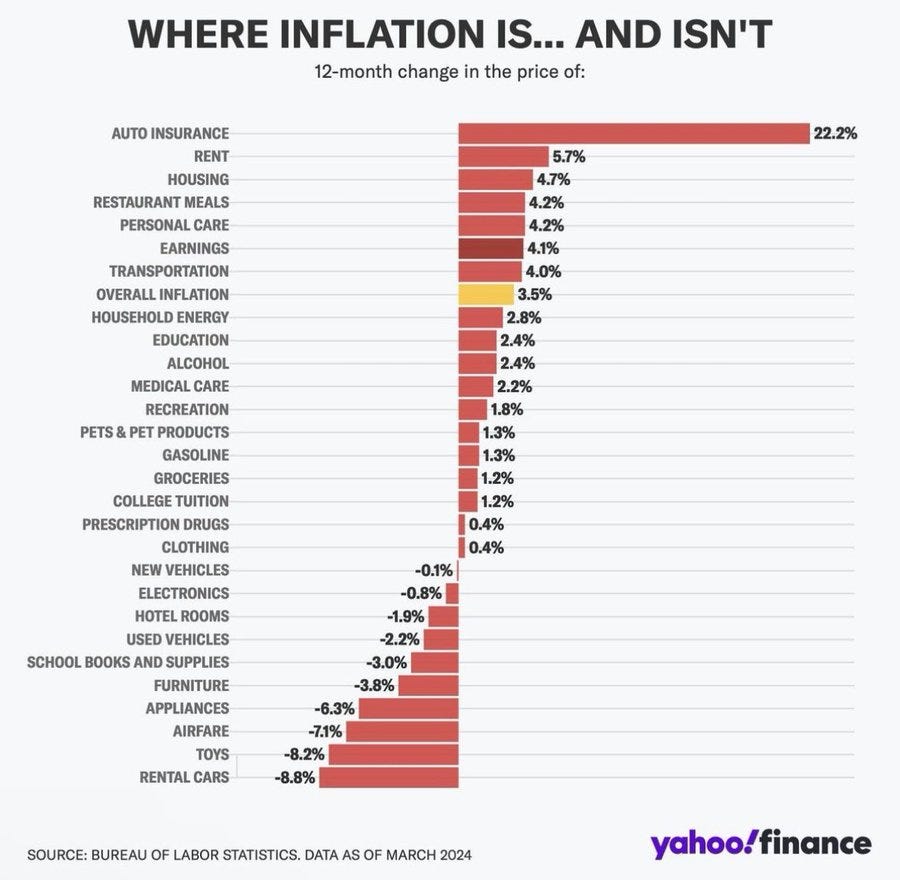

In fact, when you look at the data visualization below, you can see that the US inflation expectations are rising. At the same time, the inversion of the curve also suggests more caution in the near term on higher inflation, yet more confidence down the line.

Remember, the Fed has already hiked rates 11 times to 5.25-5.5%. The last time Fed funds were raised aggressively towards 5% in 2006-07 time period, the US housing market broke down wreaking havoc in the banking industry and generated the biggest financial crisis in the post WW2 era.

But, there is a key difference between these two periods of time. Let’s find out.

Welcome to fiscal dominance- A blackhole where monetary policy ceases to work.

One of my favorite authors Lyn Alden recently sent out a tweet saying the following:

“When you pre-stimulate an economy with $1.6 trillion in deficits, the resulting economic slowdown can look a lot different than it otherwise would.”

That is correct. The US government has been issuing Treasuries like we are in crisis times, yet the official narrative says that everything is fine. Don’t believe me? Look at this chart below.

See, unlike the 2005-2007 period, when “real economy” money creation was all about private sector borrowing, where the US private sector levered up to chase the housing bubble via the subprime mortgage and credit market engines, today the main driver of money creation is government deficits. Therefore, the risk here isn’t necessarily a major credit-led event, like we saw in the GFC. But rather, it is that the US government would keep throwing fuel on the fire, which would end up re-accelerating inflation, like we are seeing today.

Worse, interest rates are not an effective monetary tool in periods of fiscal driven money creation. Turns out, if the Fed keeps rates steady, then the federal interest expense will increase $500B throughout 2024. On the other hand, if the Fed cuts rates by 1.5%, then interest expense will increase by only $100B.

If you want to understand why interest rates are not the right monetary tool to curb fiscal-driven inflation, I had written about in one of my previous posts below.

Recently,

wrote this post, where he drew on some of Ray Dalio’s work, and organized events from “ignorable” to “decadal” to “civilizational”, where an ignorable event is a news story that someone who lived through at the time might not have registered, while a decadal event is something that shaped the decade. As for a civilizational event, we haven’t had one of those in a while.What would a civilizational event look like? According to Ray Dalio, Stanley Druckenmiller and Larry Fink, it would be a sovereign debt crisis. Plus, this recent WSJ article also acknowledges that a) there is risk in the supposed “risk-free” US Treasury bond, that b) the instability in the Treasury market is not only possible, but it could spread and that c) “many” worry about this.

In fact, just over a month ago, the CBO had released their report projecting a $1.5T in federal deficit for the entire year. Yet, as per the tweet below on April 8th, the federal deficit is estimated to total $1.1T in the first half of 2024. At this rate, the federal deficit will overshoot to $2.2T, 47% higher than the $1.5T projection. (Remember, the federal deficit is the annual difference between what the government spends and what it takes through revenues.)

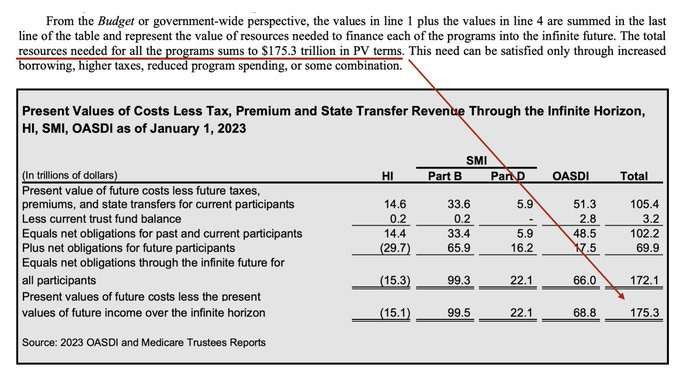

Unfortunately, it doesn’t end there. It gets even uglier, when you look at the total level of federal debt, i.e. how much the US government owes its creditors. If you thought that the highly televised number of $34T was bad, brace for impact.

“In the document below, the US Treasury itself admits that this is a sharp underestimate of what the US owes in terms of Social Security and Medicare, because it’s not accounting for future payouts decades from now. Once it does, what does the number get to? Here's the direct quote from them: "The total...sums to $175.3 trillion in PV terms. This need can be satisfied only through increased borrowing, higher taxes, reduced program spending, or some combination."- Balaji

So, no, the US government doesn’t have nearly enough to pay what it owes to its creditors, that include its allies and retirees. In order to hang on to its web of broken obligations, it will print everything that it can possibly print and seize everything that it can possibly seize, like Balaji talks about in his post, which I fully agree with.

In case you need to take a deep breath or calm down, now is the time.

However, in the meantime, the US government will continue to operate in a perceptual deficit and the US Treasury will keep issuing bonds to keep up with the demand for spending to meet its needs. After all, when a bond matures, you need to issue a new bond to pay off the principal owed to that old bond. Kind of like opening a new Mastercard to pay off your Visa. But, what happens if the demand for US Treasury bonds declines?

If you are curious, James Lavish wrote this brilliant post on what it means for a Treasury Auction to fail. In brief, it would be nothing short of catastrophic. Up until now, the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) at the Fed had served to soak up the tsunami of T-bill issuance. But, the RRP facility has now dropped from $2.5T last year to just $327B. Once this is gone, the US Treasury will have to start tapping the bank reserves, which stand at $3.5T.

And if you follow through James Lavish’s easy-to-understand logic of what happens next, then you know, what it feels like to be inside the blackhole of fiscal dominance.

“Once bank reserves drops below $1T, all bets are off.

In fact, Powell stated he starts to get nervous when they drop to $2.5T.

And with the Treasury borrowing over $2T this year, it doesn’t take a Fields Medalist (aka math genius) to see we are headed straight in that direction.

First, QT will begin to taper soon, if not already. Then it will stop altogether.

And then the dynamic duo of the Fed and the Treasury will circle their wagons, fire up the money printer and make it go BRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRR.

They will simply have no choice in the matter.

That is…

Unless they want an actual failed auction.

And I put that probability at pretty close to zero.”

The case for hard assets grows.

For the first time in decades, gold and bonds are trading in completely opposite directions. In fact, even with 4 interest rate cuts removed from market forecasts, gold is creating new highs. Odd, or completely normal?

Earlier, we saw that inflation expectations had started to rise, especially over the short term. Yet, the Fed is still posturing towards rate cuts. Craig Shapiro wrote this awesome tweet, where he pens his very well-articulated frustration on the Fed’s problematic and asymmetric policy standards.

You see, if the Fed is truly “data dependent”, as they claim they are, we should be technically pricing in much higher odds that the next move is a hike, rather than the still near 0% chance right now. Yet, the truth is, in a fiscal dominance regime, the central bank has no other choice, but to lower rates to help fund the government deficits and ensure the smooth functioning of the UST market.

In these macro circumstances, investors go and hunt for asset classes that can protect their portfolios. Gold seems to have already sniffed out this dynamic as an accommodative monetary policy to support government borrowing will likely lead to weakening of the currency and higher inflation over time.

Here is a visual where you can see how Gold has outperformed all major fiat currencies over the past century. One of the reasons for this robust performance is that the available supply of gold has changed little over time, while fiat money can be printed in unlimited quantities.

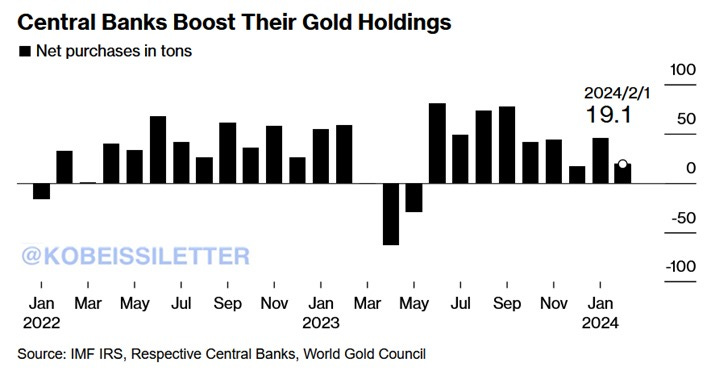

Plus, gold seems to have become a favorite of central banks worldwide, as they have increased their gold holdings for 9 straight months, as they race to improve the quality of their international reserves.

Commodities are also an obvious candidate in this regime. If the Fed is willing to ease in an economy that doesn’t need it, there are risks that growth and inflation might accelerate further down the road. As a result, we can see further inflows into commodities that do well, if inflation picks up; think copper, oil, silver.

If you are keen on understanding more about how to position your portfolio, in an environment where there is a tug of war between inflationary and deflationary macroeconomic forces, I talked about it in a recent podcast on Seeking Alpha, hosted by

.What happened to all the “productivity growth” talk? Luckily, the hope is still alive.

Shifting our focus to the beacon of optimism, despite the inflationary forces of a fiscal dominant regime, there are also signs that the US economy may be entering a period of prolonged productivity boom.

I wrote about this in my “Don’t bet against America” Part 2 series, where I discuss at length how macroeconomic forces need to align together to set the foundation for long-term productivity gains, taking the 1994-2000 period as the historical benchmark.

Specifically, the US needs to be able to sustain at or near full employment conditions, so that businesses have the incentives to invest in innovation and technology in order to increase production capacity to meet consumer demand, while supply-side inflationary shocks remain more or less controlled, in order to prepare for long-term productivity liftoff.

Last month, the US economy added 303,000 jobs, the highest in three months. In fact, over the last 3 months, the US economy is adding jobs at an average pace of approximately 275,000 per month, higher than the average pace in 2023.

But contrary to mainstream claims, this doesn’t mean that “the labor market is very tight”. In fact, the labor market is getting bigger, not tighter, as labor force participation inches up (though still below pre-pandemic levels).

The evidence also shows up, where 1) Average Hourly Earnings are continuing to grow at a slower pace, up 0.3% MoM, 2) the difference in wage growth between “Job Switcher” and “Job Stayer” continues to shrink, while 3) quit rates sit at pre-pandemic levels.

You see, a tight job market sees rapid wage growth and people looking to jump ship at the first opportunity with voluntary quits. That is not the case today.

Let’s provide another layer of context by extrapolating the total number of Non-farm payrolls based on the pre-pandemic trend. In February 2020, the total number of US non-farm payrolls stood at 153,309M employees right before the pandemic. Assuming that Non-farm payrolls grow at par with real GDP growth of 1.8-2%, we should have been close to 164M non-farm payroll employees today, had a Covid-led recession not occurred. In other words, 4 years after the Covid pandemic, we are still tracking 4% behind the pre-pandemic trend.

This means that the US economy can sustain higher job creation without stoking pay pressure. This will be hugely beneficial for long term productivity growth.

And then there’s AI, which is a double-edged sword, walking a thin line between the promising disinflation era that it might bring or the much feared creative destruction and deflation period, as the marginal cost of creation goes to zero.

Here’s a fun fact: Did you know that the visual effects team on Everything Everywhere All At Once, last year’s quirky Best Picture winner, used the AI tool Runway on the film? It is one of the reasons that the movie was able to be made with just seven people (five full-time, two contracted) on the VFX team. This is an example of doing more with less, while the size of the economic pie grows with augmentation and lower cost of experimentation.

Tying it together: Is 3% the new 2%?

The US economy is in a state of acute divergences. Think about it. 🤔

On one hand, if the Fed cuts interest rates prematurely to help the US government lower its interest expense burden, it risks ushering in higher inflation and possibly destabilizing inflation expectations. On the other hand, the longer the Fed keeps its rates high, it can trigger a regional banking crisis, especially those that are most exposed to Commercial Real Estate (CRE) loans.

Similarly, while high-end Americans are loving life, with a stock market wealth effect, house prices near record highs and cash to spend, the low-end consumer confidence is in recession territory. In addition, high-end consumers still have excess savings, supporting consumer spending.

Travis Kling, Founder and Chief Investment Officer at Ikigai Asset Management wrote this fabulous piece on Financial Nihilism, where he explains it as follows:

““Financial nihilism”- the idea that the cost of living is strangling most Americans; that upward mobility opportunity is out of reach for increasingly more people; that the American Dream is mostly a thing of the past; and that median home prices divided by median income is at a completely untenable level.”

We can see the concept of “financial nihilism” manifest in consumer behavior, where gambling is becoming increasingly popular with lottery ticket sales at a record high. Not to mention, the popular philosophy of “Die with Zero”, popular among GenZ’ers that promotes the idea of net fulfillment over net worth, with the rise of payment forms like “Buy Now, Pay Later” (BNPL) and increasing credit card debt.

The divergence is equally stark when it comes to organizations, where S&P 500 companies are materially better off than small-caps, with many having tremendous pricing power to keep prices high, while nearly half of the small cap universe is unprofitable with an average Net Debt/EBITDA ratio of 2.5x, double that of the S&P 500.

outlines the following in his post which captures the idea.

“In 2023, PepsiCo’s chief financial officer said that even though inflation was dropping, its prices would not be. Pepsi hiked its prices by double digits and announced plans to keep them high in 2024.

If Pepsi were challenged by tougher competition, consumers would just buy something cheaper. But PepsiCo’s only major soda competitor is Coca-Cola, which — surprise, surprise — announced similar price hikes at about the same time as Pepsi and has also kept its prices high.”

We’re seeing this pattern across much of the economy — especially with groceries. At the end of 2023, Americans were paying at least 30 percent more for beef, pork, and poultry products than they were in 2020.

Why? Near-monopoly power. Just four companies now control processing of 80 percent of beef, nearly 70 percent of pork, and almost 60 percent of poultry. So of course it’s easy for them to coordinate price increases.

The problem goes well beyond the grocery store. In 75 percent of U.S. industries, fewer companies now control more of their markets than they did 20 years ago.

There is no doubt that the Fed’s mandate of price stability and full employment will become more difficult to manage as we navigate this environment of intense push-pull macroeconomic factors.

But, in the short-term, I don’t see a high probability of a rate hike or the more headache-inducing procedure of the Fed raising the inflation target. I personally think that the Fed will likely remain put, while still maintaining its expectations to cut rates 3 times in 2024. Or in other words, do nothing.

Unless of course, we see a supply induced inflationary shock (think: geopolitical tensions), or an immediate banking meltdown (SVB like instances, but with CRE loan portfolio).

You see, although inflation expectations in the short term have gone up with higher CPI prints, it is still pretty well-anchored over the longer time period. Meanwhile, the long end yields have started climbing higher, to reflect rising premiums. This is essentially a demonstration of the bond market doing the Fed’s job of tightening in the short term, without the Fed having to actually hike its federal funds rates. Take a look at Mortgage applications, for instance that have plummeted, given rising 10Y US Treasury yields.

At the same time, we also need to mindful of how high the long-end yields can climb from here, if inflation continues to overshoot target, although that is not my base case. In the recent shareholder letter, Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase cautioned about long-end yields saying the following:

“If long-end rates go up over 6% and this increase is accompanied by a recession, there will be plenty of stress — not just in the banking system but with leveraged companies and others. Remember, a simple 2 percentage point increase in rates essentially reduced the value of most financial assets by 20%, and certain real estate assets, specifically office real estate, may be worth even less due to the effects of recession and higher vacancies. Also remember that credit spreads tend to widen, sometimes dramatically, in a recession.”

I personally don’t think we are going to see too much of a steepening in the yield curve for much longer. Having said that, it is imperative that the Fed continue to focus on lowering inflation now.

Earlier this month, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development issued its annual report where it said the following:

“Central bankers should relax their 2% inflation target and assume a wider stabilizing role,” the Geneva-based group declared, lamenting that “tighter monetary policy has so far contributed little to price easing, but delivered a steep cost in terms of inequality and damaged investment prospects.”

As geopolitical tensions reshuffle supply chains in an inflationary manner, central bankers are increasingly faced with the problem where prices are no longer shaped by demand cycles, but by supply issues, for which they have far fewer tools. Therefore hitting 2% inflation target would mean far bigger rate increases, that is far from ideal in a fiscal dominant regime. Not to mention, the death of productivity gains as well.

But shifting to a higher inflation target is not so simple either. In fact, if it is not done in a manner that is credible, it could disrupt inflation expectations, leading to soaring inflation premiums for borrowers, driving up government’s deficits and reducing private investment. I believe that if we are to eventually move to a higher than 2% inflation regime, it is imperative the Fed makes it clear that it isn’t raising the inflation target merely to avoid the pain of getting inflation down, and that it sticks with it. It wouldn’t work to announce, say, a new target range for inflation of 2% to 3% and end up with 3.5% inflation. It would threaten the Fed’s credibility.

For now, the more successful the Fed is in fighting inflation now, the more room it will have to make the right long-term moves for the U.S. economy.

Tell me what you think!!

That’s all for today, folks. Hope you found this post useful.

Please leave your thoughts in the comments section below.

Amrita 👋🏼👋🏼

What a piece of excellent research, Amrita! Wow! There is so much to unpack.

1) While gold has outperformed major fiat currencies, let's not forget that gold has been a lousy investment, a lousy inflation protector, a lousy crash protector, and a lousy diversifier for both stocks and bonds over the past 40 years. The only time it has been a great investment is during periods of expected economic slowdown with the anticipation of a soft landing, which seems to be happening now. During such times, gold has delivered double-digit returns almost every time.

2) I’m surprised I don’t see health insurance among the inflation drivers, unless the BLS combined it with medical expenses. Health insurance premiums have been growing at around 4%, and with my luck, my personal insurance premiums have been growing in the 10-12% range.

3) I’m also surprised that education prices grew at only 2.4%. I suspect the BLS may have combined subsidized and non-subsidized education, which is incorrect because I believe only the top-level non-subsidized prices should be reported, or at least reported separately.

I don't get why the "national deficit" matters. It never seems to matter when bailing out banks or giving the pentagon 1T a year. It only matters when it comes to paying for pensions or health care when we "can't afford" it.